I’m not sure if it’s because I’m lazy that I like to read books I’ve already read, or because I’m a student of the craft of writing. Or maybe they’re both the same reason: literary critics are lazy sorts. But I do enjoy re-reading books that I’ve already read, often ones that I’ve already re-read several times.

Armed with a dim memory of the basic plot, I find that I’ve forgotten how most of the chapters, paragraphs, and sentences were formed, and it’s a delight discovering these writerly techniques a second time, and sometimes a tenth time. I feel as I did as a small child having the same comforting stories read to me night after night, only these stories are now often convoluted narratives that seem slightly deeper or more rewarding on every re-reading, with different emphases than I gave to them before.

I’ve taken to re-reading Bill James’ explanations of baseball dating from the early 1980s, even though the author himself has explicitly disavowed these texts, in part or in whole. He claims not to agree with what he wrote three or four decades ago, which only makes sense, as I find I don’t agree all the time with my beliefs of three or four minutes ago. He’s also justly proud of having made the discoveries he has—which is no paradox. One may disavow particular passages in a larger work whose overall thrust is perceptive. More often than we usually do, we should regularly disavow such passages. "I was nutty here," or "Who knows what I was thinking?" or "Which drugs was I taking when I came up with this line of crap?" But even if some key elements in the narrative have changed since the 1980s, it’s still a pleasure because 1) 98% of it holds up just fine, and 2) the clarity and tone of the other 2% remains artful.

Some of this pleasure is just nostalgia, of course, reliving the delight of coming across these concepts for the first time, and my astonishment in seeing them put into such well-crafted words. But mostly it’s just respect for the insights themselves, insights I had absorbed and then, over the years, forgotten (or assumed I was born knowing). Just now, tonight, in fact, I was reading a treatise from 1980, and was knocked out by the rationality and the lucidity of the explanations—it wasn’t about baseball, though. I was re-reading Carl Sagan’s book Cosmos. I’m such a scientific and mathematical ignoramus that I can’t really follow the technical details when Sagan explains how Isaac Newton invented calculus, but honestly I usually skim Bill James’ step-by-step explanations of how he dealt with problems that cropped up along the way and how he resolved each of them. And, like one of Bill’s fiendishly complex explanations, Sagan’s passages running down problems of 1980s cosmology and his resolution of them, I’m sure, require updating and tinkering and even negation from time to time. When Sagan speculates on the findings of Voyager, well, I’m pretty sure that later ships we sent out to explore space have sent back data augmenting those initial findings and in some cases even contradicting them. After all, there’s a reason we kept on launching these things into outer space, isn’t there? Having shot a ton of metal into space, the NASA guys didn’t pat each other’s backs and say, "We did it. Why do it again?" The answer to that question is plain: to gather new data that will surprise and puzzle and upset our preconceptions.

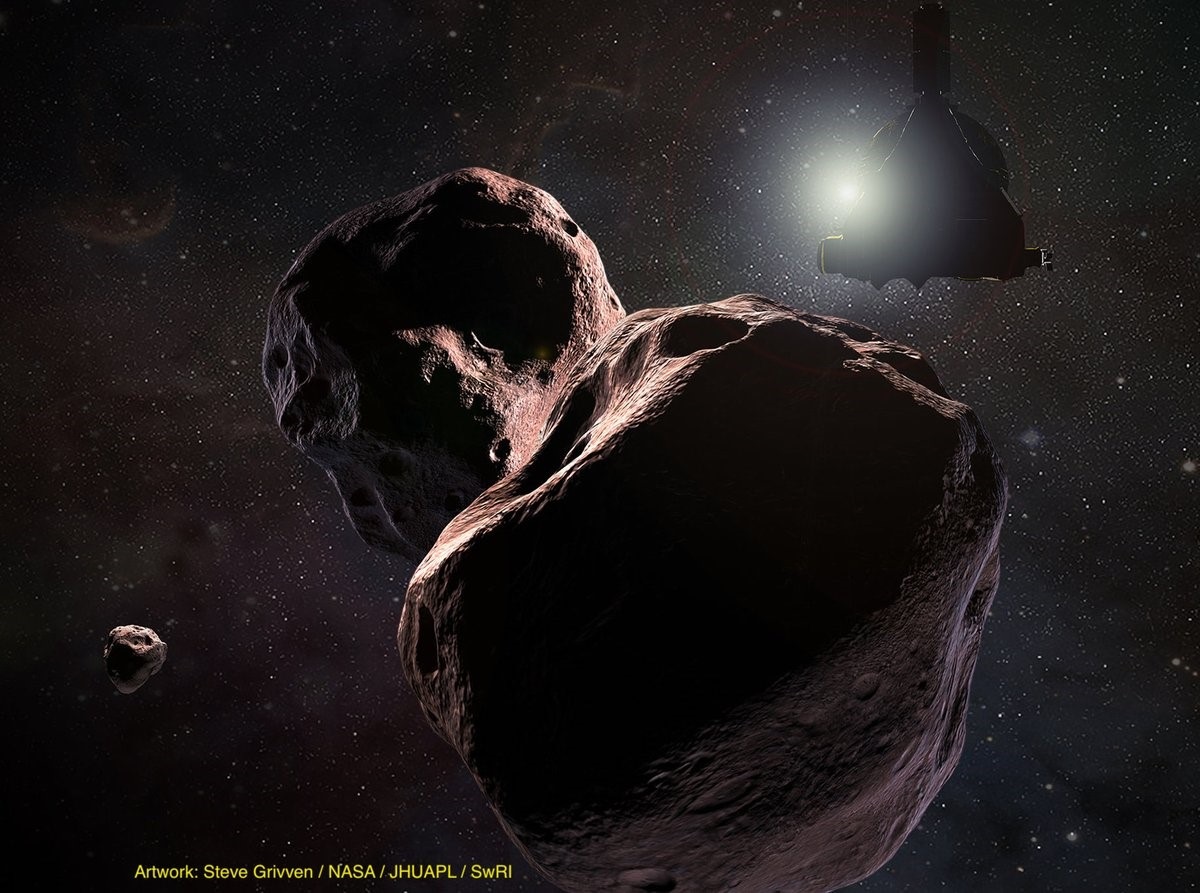

As a matter of fact, almost immediately upon writing the paragraph above, I learned that a spacecraft launched 13 years ago (or twenty-six years after Cosmos was published) just took the photograph below of an incredibly ugly asteroid in the Duane Kuiper-Brandon Belt area of outer space (it looks like some misshapen skull of a two-headed anthropoid, don’t it?) that astronomers are going ape over.

But new stuff doesn’t invalidate Sagan’s older stuff, and I’m so ignorant that even learning old stuff is new to me, and represents the history of scientific thought: we used to think X, but now we think Y. Or: We used to think X, but now we think X+24. If you’re interested in reading what a scientist rather than a rank amateur makes of the progress in cosmology since Sagan had at it, you might want to look at this essay: https://www.quora.com/Is-there-anything-in-the-original-Cosmos-series-by-Carl-Sagan-that-is-now-known-not-to-be-correct, which updates Sagan’s findings since the 1980 publication of Cosmos, detailing the new understandings we’ve learned since then about outer space. (When I was a kid, I lived in a neighborhood where "outer space" was pronounced the same as "out of space," so the concept was inherently more mysterious to Brooklynites than to lesser mortals. We sort of understood from the very beginning that "space" might be recursive and not simply an infinite extension of the space we’re all familiar with. Sagan, just incidentally, comes from the same part of Brooklyn I do, and I can hear a distinct tinge of Bensonhurst in his narration. https://bklyner.com/video-carl-sagan-recalls-how-bensonhurst-upbringing-sparked-love-of-cosmos-bensonhurst/) I find it fascinating to go back and see where new data has shown Bill James’ ideas about baseball to be off, or incomplete, or utter mistaken.

That’s where Bill’s insights intersect with scientific methods, sort of like Edison’s response to failing to find a substance to make a filament out of: "I have not failed 10,000 times," Edison allegedly asserted. "I have successfully found 10,000 ways that will not work." Sometimes Bill sets out to examine some truism of baseball, expends enough energy to launch a 40-unit condominium into orbit, and finds that he didn’t learn a blessed thing about the truism but has, along the way, discovered something entirely different and useful. That seems like the scientific method to me.

Bill dislikes re-visiting his greatest hits—he flat out refuses to review stuff he wrote long ago, but approximately as little as he likes rehashing his older stuff, I like rereading it, and once in a great while, I spot something he wrote long ago that warrants discussion now. On p. 156 of the Win Shares book, he wrote about Total Baseball’s flawed estimation of defensive innings played, and how it fatally screws up their defensive assessments—for example, TB made Steve Garvey out to be a superior third baseman in 1971 by estimating that he played 514 innings at third base. Bill figured that "Garvey in fact probably played about 599 innings at third base in 1971," which made Garvey’s ratio of plays:innings much less impressive, if not downright rotten.

From the context and Bill’s frustrated tone, I’m guessing that in 2002, when Win Shares came out, no one had gone back yet and calibrated the innings that Garvey, or anyone, actually played, but now we have Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet doing all our old scut-work, so I can update the actual number of Garvey’s innings at 3B: 560.2. Bill’s estimate was 38.1 innings too high, TB’s was 45.2 too low, nothing to brag about there either way, except for Bill’s larger point, which was that we can’t estimate accurately someone’s defensive innings by looking at his plate appearances, because PAs will be manipulated by a bad fielder’s manager to be disproportionate to his defensive innings.

Since we were just guessing at players’ total innings played at each defensive position when Bill first grappled with this problem, it’s sort of interesting to review some of the specific points he addressed in that chapter, and see how the more recent stats affect the evaluations.

"The Dodgers’ two most used third basemen," he goes on to write, "in 1971 were Garvey and Dick Allen." He cites Garvey’s total putouts + assists at 3B (214) and Allen’s (169) to assert that "it is unlikely that Player B [Allen] has played more innings at the position than Player A [Garvey]." Unlikely as it was, Allen DID play more innings than Garvey at 3B in 1971, though the anti-climactic truth is that Allen and Garvey would have had a very hard time coordinating a closer finish in innings played if they had planned it with a slide rule every night for a month: Allen led the Dodgers with 561.2 innings and Garvey finished exactly one inning behind:https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/LAD/1971-fielding.shtml#all_players_standard_fielding_3b. (Sorry to keep using this awkward way of referring to thirds of an inning by the decimal system, making it appear that Garvey and Allen each played two-tenths of an inning at 3B somehow in 1971, but that’s what BBref uses, and I’m trying to be consistent in my quotations here.)

The virtual tie undercuts the argument (if Bill was making it) that Garvey’s stats at 3B were worse than Allen’s: on a per-inning basis, Garvey out-fielded Allen in every regard, more assists, more putouts, fewer errors, though both men got moved off 3B permanently after 1971. They both got shifted over to 1B in succeeding seasons, so you’d have to judge both of them as failing to pass the audition as minimally acceptable third baseman in 1971. (Garvey continued to audition in 1972, after which he never played 3B again, while Allen went on to play exactly 2 innings at 3B for the remainder of his career.)

Let’s look at Yogi Berra’s last few years behind the plate, because Bill uses Yogi as his next example of weird defensive assessments that Total Baseball makes on account of mis-estimating innings. It’s kinda mindblowing realizing that in 2002 we were still guessing at players’ defensive innings based on their games, plate appearances, and other data that only hint at the innings, but that was one of the problems in developing the Win Shares system, at least defensively. Bill came up with some ingenious work-arounds, particularly his "claims points" technique that he details from pp. 158 through 160 of the book, to estimate defensive innings more accurately than Total Baseball did. But it was a far cry from actually knowing the number of defensive innings played. "The only possible explanation," Bill explains (p. 157) of TB’s judgment that Berra played a world-class-brilliant defense at catcher in 1962 and 1963, "is that they tried to estimate his defensive innings and missed badly, causing all of their defensive calculations to misfire."

The main culprit in such mis-estimations across the board was the problem caused by players sharing positions: if the best information you have available is that players A, B, C, and D collectively played 230 games at one position, and players B, C, D and E collectively played 198 games at another position, while players C, D, E and F combined to play 216 games at a third position (and so on), all batting for just above or just below the number of expected plate appearances for their total "games played," how accurate could you possibly be in figuring out their defensive innings at each position?

Answer: Not very accurate. Everyone’s rationales for how to deal with the estimation problem get themselves boxed into logical contradictions, dead-ends, spurious reasoning processes, with many despairing hands thrown into the air. Berra’s defensive assignments in 1962, for example, are among the strangest figures I’ve ever seen, but for the opposite reason that Bill cites. His contention that Berra was switched in and out of the lineup constantly, making his innings at each position impossible to estimate, seems plausible at first: Berra caught in 31 games, played LF in 28 others. An aging catcher who could still hit a little bit, Berra looks on the surface like he backed up the Yankees’ starting catcher, the younger (though not young) Elston Howard: backup catchers often enter games late as defensive replacements, or pinch-hit for the pitcher and then stay in the game behind the plate, or enter games when they become blowouts to save wear and tear on the #1 guy—but no, not in this case.

Berra’s 28 games in left field in 1962 suggest also that he filled in for the regular LFer, or played the second game of doubleheaders, or substituted for a right-handed batting LFer facing a tough righty, etc. You look at those figures, 31 games at one position, 28 games at another, and the picture in your head is that Berra might have played a bunch of games where he started in LF, got switched to catcher for a few innings (or vice-versa), or came into the game as a pinch-hitter and played a partial game at either position, making for a logistical nightmare in computing his defensive innings at C and LF. That’s certainly Bill’s point in citing Berra’s 1962 as an example of the difficulty in estimating defensive innings.

But despite splitting his playing time about equally between two positions, Berra actually switched positions in-game 0 times in 1962. There was only one calendar month, let alone game, in which he switched positions. In April and May, he was a starting LFer, playing 18 games in LF, which he continued into June, playing another 10 games in LF through June 17th. Up until that point, he hadn’t caught a single inning of a single game. But on June 19th, he suddenly became a catcher exclusively, and stopped playing LF completely: from that point on, he caught 28 games. It’s like they sent their part-time LFer to the minors on June 18th and brought up a new backup catcher.

Yogi came into exactly one game as a pinch-hitter and then played LF (on May 20th) and did the same as a catcher (on September 11th)—otherwise, he pretty much finished the games he started at each position. His in-game switches, in other words, didn’t even exist, and so present less of a dilemma for analysts than almost any other multi-positional backup player in history. A complete defensive game isn’t exactly 9 innings, since losses on the road will call for only 8 defensive innings, which get compensated for by some extra-inning games, so you can see that Yogi averaged almost exactly 9 innings at catcher per defensive game by dividing his innings at catcher by his games: 271 innings in 31 games. He played very few partial games at catcher—in fact, for a 37-year-old guy with 1600 games in shinguards behind him, he caught a superhuman number of marathon games in 1962 from beginning to end: among his five extra-inning games that year were a 22-inning monster against the Tigers on June 22, a 16-inning epic against the Red Sox on September 9th, and a game against the White Sox on August 5th that ended with two outs in the thirteenth inning. He was clearly capable of playing a full game (and more) behind the plate, and that’s exactly how he was used in 1962, not as a guy flitting in and out of the lineup.

BTW, I have a new complaint about Baseball-Reference’s statistics, which seem particularly and needlessly stupid to me: they run two columns side-by-side on their "team fielding statistics" pages, individual "G" (games at a position by each player) and "GS" (games that each player started at that position), which makes sense, but they total both columns to read "162" (or whatever the team’s total games were that year). Of course "GS" will equal the team’s total number of games played, but why on earth wouldn’t BB-Ref.com take the trouble to add up the number of "G"? The difference between the two numbers is crucial for understanding how often the players switched positions in-game, and it’s only simple addition (and looks like hell besides, adding 64, 43, 28, 15, 14, 6, and 20 to get 162. The seven leftfielders the Yankees actually used in 1962, Berra being the 28 in that sequence, combined to play 190 games, meaning that they switched left fielders 28 times during games that year. I have no idea why baseball-reference decided it would be good to make me add that column up in my head in order to write this paragraph.) It’s actually interesting information, telling me that Tom Tresh played 43 games in LF, started all of them, and played all but one to the game’s end—in other words, he was rarely taken out of the game for a defensive replacement, while Johnny Blanchard played and started 15 games in LF, but finished only five of them. That doesn't speak very well to Blanchard’s defensive skills in the outfield, but it speaks very favorably of Tresh's.

On the other hand, Jack "Mickey Mantle’s Legs" Reed was used in LF exclusively as a defensive replacement, 20 games, 0 starts, and only 31 innings. Of those 20 games, he finished all of them in LF. Bill’s guess that Reed "probably didn’t play 50 innings on defense" in 1961 is off, though not significantly—Reed played 61.1 defensive innings that year. Bill’s main point about Reed, however, still holds despite that quibble: Total Baseball makes him -9 runs as a defensive player in 1961, so "it would be questionable if the other teams even scored 9 runs when he was in the field, let alone 9 more than they would have scored with a better center fielder." Actually, it would be pretty remarkable if the other teams didn’t score over 9 runs in 61.1 IP, since that would yield only 1.32 Runs Per Game, but Bill’s sarcasm doesn’t weaken his point: TB’s methodology in estimating defensive innings sucked. What I think happened in 1961 for Reed was that he committed one error in only sixteen chances, giving him a much-below-average fielding percentage, so if Total Baseball also credited him with playing too many defensive innings, he looked like a guy who didn’t have much range and didn’t have good hands. In reality, he probably had above-average range and above-average hands—why would the World Champions employ a defensive klutz to play late-inning defense?-- but you’d never know it from looking at the small sample of his defensive work in 1961.

Anyway, the other year Bill cites in Win Shares for Berra’s statistical defensive anomalies, 1963, is even more straightforward, since the now-38-year-old caught exclusively in 1963, no LF at all. And again, he was very rarely shuffled in or out of the lineup: of his 35 games, 28 were complete games, and of the other 7, he played six defensive innings or more four times. His total stats at catcher in 1963 were 292 innings in 35 games, or an average of 8.3 innings per game—it’s hard to see how much allowance we’d need to make for Berra going in and out of the lineup on that basis. Rather than make a series of convoluted adjustments based on plate appearances, it seems much more straightforward just to assume that whenever Berra caught a game, he caught the entire game, and to deal with his numbers without any adjustments or corrections or estimates, which is where Total Baseball seems to have erred, making elaborate corrections to a stat that didn’t need correction. (When the Yankees made Berra a catcher exclusively in 1963, they also consigned Johnny Blanchard to the outfield, after having each of them play both positions in 1962. I wonder what made Ralph Houk deploy his catcher/outfielders so differently in the two years.) Bill’s issue with Total Baseball’s evaluation of Berra in 1962 and 1963 is that they WAY under-estimated his actual defensive innings, and thereby credited his rather mundane defensive stats as taking place in a context of far fewer chances than he actually had. Even still, some of his stats were terrible: Berra threw out only 18% (3 of 17) of the runners who attempted to steal against him in 1962, which you would think would have counted for something in their assessment of his catching as "superb." As Bill correctly points out, TB made Berra in his old age out to be the greatest defensive catcher of all time, which seems a little much just on its face. If that’s the conclusion you reach, a guy with good defensive stats suddenly becomes a world-class catcher in his late 30s, you should probably be asking yourself, "OK, where did I screw up here?"

Bill didn’t need to be right in order to point out how wrong Total Baseball’s approach was, and he often wasn’t right. What he was, was sensible. He castigated Total Baseball (but nicely, because he still respected Pete Palmer personally and professionally, even if he found his methods here outlandish and unreasonable) for failing at times to apply the good sense that God gave a mollusk. How someone could suggest that Jack Reed cost the Yankees 53 runs over the course of a career that lasted only 600 innings (Bill’s estimate—actual number was 509 and change) is bizarre, but Palmer not only suggested it, he committed it to print in a reference book. Win Shares is actually a great guidebook in etiquette: how do you politely point out a colleague’s atrocious professional judgment, and still avoid being abusive and offensive to him? I often face that problem myself, sometimes in the university, sometimes at academic conferences, sometimes here on BJOL, and I don’t tread that fine line nearly as well as Bill—my critical comments often sound too much like snide abuse, while other times I bend over backwards so far to seem kinder than I feel that that my criticism gets stifled entirely. Just yesterday, on John Thorn's Facebook page, I corrected someone's misquotation of Casey Stengel's clever crack about Greg Goossen being 20 years old and having a chance in ten years to be 30, thus igniting a flame-war that ended in poor John having to erase his entire thread. If you're reading this, John, my apologies.

Pointing out others’ lapses in applying good judgment in assessing fielding stats, however, Bill boxed himself in a little bit at times. Apart from its value in running the tables of every player (through 2002, of course) who ever played the game and the Win Shares he earned in each season, which I still refer to, the book’s "Random Essays" are unforgettable: Mays or Snider, Mazeroski or Randolph, Ashburn or Hamner, Tresh or Delahanty are all classic essays to my mind. BUT: in the essay on Roy Smalley, another small classic, he comes to a conclusion that he had forcefully rejected a few years earlier when a reader (not me) suggested that Larry Bowa merely seemed to have limited range because he was playing next to Mike Schmidt, who had great range. Here (p. 186), Bill adopts the reasoning that he had formerly rejected: "Obviously, if Belanger is playing in the middle of a bunch of other guys who can also go after the ball, that drives his fielding opportunities down…." If it’s such a dumb idea about Bowa and Schmidt, how did it get to be a good idea about Belanger and Brooks Robinson?

This essay contrasts Smalley with Mark Belanger, who often was pinch-hit for and so missed a lot of innings in the field. Smalley, who swang a mean bat, was never pinch-hit for, but they each had very similar numbers of "games played." Missing the data for "innings played," Bill maintained, was the key to understanding their similar defensive stats. He cited their 1977 fielding stats:

|

|

Games

|

Putouts

|

Assists

|

Errors

|

DPs

|

Range

|

Fielding pct.

|

|

Smalley

|

150

|

255

|

504

|

33

|

116

|

5.06

|

.958

|

|

Belanger

|

142

|

244

|

417

|

10

|

82

|

4.65

|

.985

|

and he tried to explain how Belanger was nonetheless the better fielder. The relevant (and missing) figure is their "innings played," which we can now supply:

|

|

innings

|

PO + A

|

RF/9

|

|

Smalley

|

1325.3

|

759

|

5.15

|

|

Belanger

|

1089

|

661

|

5.46

|

Going on the cruder stats available in 2002, Smalley appeared to make about a half-play per game over Belanger, but now, on a per-nine-innings basis, appears to have made a third of a play fewer than Belanger. In addition, of course, Belanger had a considerable edge over Smalley all along in terms of their error frequency, so now, as Bill’s article asserted, we can easily see that "even in his mid-thirties, Belanger was better" without Bill’s need in 2002 to show how "games played" mispresented each man’s time in the field. As to Smalley’s seeming advantage in "doubleplays turned," Bill explained that Minnesota had far more men on base than Baltimore—this "new" data just confirms Bill’s conclusion about which shortstop was the better fielder.

The entire section of Win Shares that dealt with the mis-estimation problem is now obsolete, but that doesn’t make it any less fascinating. Faced with a problem in 2002 that would have baffled every one of us, at least those of us now wearing a pair of my underwear, Bill dispatched the problem with solutions that, while often mistaken or incomplete, provide hope for all of us when facing similar problems: try a method, and when that fails, try another, and another yet. If you show the world your work attempting to solve the problem, you can stimulate thinking and in this case, you might even still stimulate the world to count the defensive innings of every player who ever played an inning of MLB.