(This is the text of a speech I delivered April 1 at a baseball fiction academic conference in Ottawa, Kansas.)

This talk is about a dead dream of mine. Since the 1970s, I have been fascinated by the notion that meaningful fiction could be created with numbers, or, to be more technically accurate, could be created in the form of a Baseball Encyclopedia. Baseball statistics, more than the statistics attached to almost any other human activity, or entirely unlike other statistics, have the capacity to create stories. The reason this is true is that the way that baseball statistics are processed by most people most of the time is as images of different skills and character traits.

Take, for example, the number "40" if it appears in the "Home Run" column. This doesn’t refer to 40 of anything; well, it does, but it is not taken that way. Forty in the home run column means POWER, great power. Twenty in the home run column means "power"; 30 means "real power", and 40 means "great power". A 50 means "historic power".

So it is with each number in each column of a player’s record; the number represents not an accounting of how many times an event has occurred as much as it represents the characteristics of the player which made those events possible. A "50" in the stolen base column represents speed, outstanding speed. A "30" in the stolen base column represents speed; an "80" represents historic speed. A "15" in the triples column represents both speed and an ability to hit a slashing line drive.

When we see a player’s batting record, we are searching that record for the answers to questions which have really nothing to do with numbers: How fast does this player run? How strong is he? How well does he read and react to a pitch? Is he learning, is he improving, is he getting better, or is he going backward? Is he figuring out the league, or is the league figuring him out?

Each single number on a player’s record has meaning in this way, and therefore a chart of numbers, tracking what the player has done over a period of years and in 12 to 20 different areas, has the capacity to tell a story, in the same way that a paragraph of words has the capacity to tell a story, only, I would argue, more so. It is more so because there is inherent meaning in the arrangement of the columns and in the form of the record.

Baseball statistics can be keys not merely to physical attributes, but to character and personality. If a player is exactly the same year in and year out—that is, if he is CONSISTENT—like Gil Hodges, Henry Aaron, Luis Aparicio, Bobby Abreu or Tom Glavine—it may be assumed that he is a solid, stable, mature individual; I suppose this could be proven untrue, but I don’t know of any case in which it was untrue. The consistency of the record can be seen as a psychological test of consistency, although we should note that there are in fact stable, consistent people who have highly inconsistent records because of injuries and other factors. If a player controls the strike zone and maximizes his performance in other related ways, it may be assumed that he is probably an intelligent person, although I have certainly seen cases in which this did not seem to be true.

Now, at some point you will object that the range and variety of stories which can be told in this form is more limited than those which can be told with words, and this is no doubt true. The general limitation of baseball fiction is that it focuses on things that happen to young men between the ages of ten and thirty-five, and things like girlfriends and mothers and juvenile arrests and crises of faith are structurally peripheral to the narrative.

I was trying to explain this concept to a friend a few months ago, and what my friend thought that I was saying was that charts of numbers can be created on which fiction can be based; in other words, that one could take each chart of numbers and imagine, based on that, the life and career that the player could have had. But that’s not exactly it. What I am actually arguing is that the story is created—the FICTION is created—by the numbers themselves. While of course that story can be enhanced and developed by words, just as a story told in words can be enhanced and developed into a movie or a TV show or a comic book. …while of course that story could be enhanced and developed by words, the chart of numbers ITSELF represents the fixed posts of the story which give it its inherent shape, and much of its original detail.

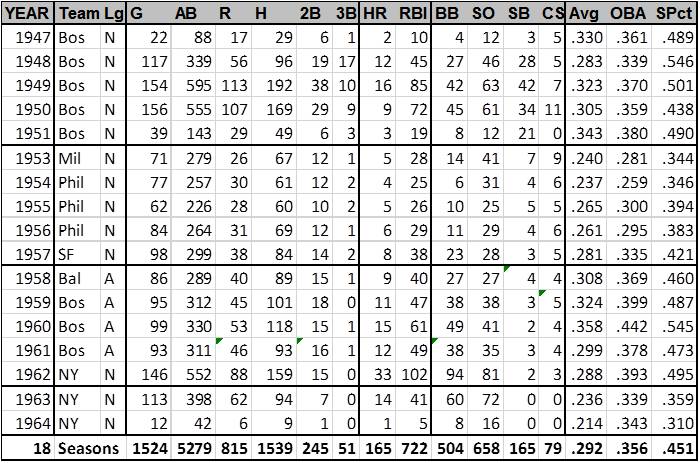

I have probably gone as far to explain that without an example as I can, so let me give an example. Let us take the player that I have marked as Player 1 on the handout.

If you read through this player’s record, his story is told here in substantial detail. He was a young player who came up with the Boston Braves at the end of the 1947 season, and had a tremendous first month. He was a 4th outfielder as a rookie with the Braves in 1948, played OK. He was a blindingly fast runner as a young man. We know that he was blindingly fast because he hit 17 triples as a part-time player in 1947, which is a very, very high number, and he stole 28 bases that season and 42 bases the next season. These are things that you cannot do unless you are a fast runner.

He was also a good hitter, on the margins of being what we might describe as a great hitter, and for the next two seasons he seemed to be en route to a distinguished career, even a Hall of Fame career. Early in the 1951 season, however, he suffered a very serious injury. Having already stolen 21 bases in the first 39 games of that season, he missed the rest of that season and all of the next season with what we must assume was a devastating leg injury.

In the main, I am trying to stress that this is not an optional reading of this chart of numbers, but a necessary and inevitable reading of this chart of numbers. There is no way that these words could not be true, although there are no words in the chart. However, there is an alternative reading here of the short season in 1951 and the missing 1952 season. There were players in that generation, including Willie Mays, Don Newcombe, Whitey Ford and Curt Simmons, who had shortened seasons about 1951 followed by seasons that were entirely missed due to the Korean War. It is POSSIBLE, although this was not my intention, that the player described here did not suffer a serious leg injury in late May, 1951, but rather than he was drafted into the United States Army at that time. But that’s OK; my understanding of the rules of fiction is that some ambiguity in a character’s history is acceptable.

Returning now to my narrative in words of Player 1, when he returned to the game in 1953 he was not the same player. He was no longer fast; the leg injury has taken his speed away from, although perhaps it was an injury suffered in action in Korea, but in any case he no longer ran well. He had to cope; he had to adjust. His team had moved from Boston to Milwaukee, and they had other young players that they placed more value on. We know as baseball fans that in the winter of 1953-54 this team had a 20-year-old outfielder named Hank Aaron, although this knowledge is not directly given by the chart. In any case, our player was traded to Philadelphia that winter, and resumed his career at a greatly reduced station in life, as a reserve outfielder. He was not a particularly good reserve outfielder, at first, but over the years he gradually re-tooled his game. He became a more selective hitter, and worked on developing his power game, since his speed was gone. He gradually became a top-flight fourth outfielder in the model of Jerry Lynch or Wes Covington. He was traded to the American League, where he was a fourth outfielder from 1958 through 1961.

In 1962, at what we know must be an advanced age for a baseball player although we do not yet know what it was, he finally got the opportunity to play regularly for the first time in many years. This was due to expansion. What I will assume that you all know, although many of you may be foggy on the details, is that the National League expanded in 1962, creating the New York Mets. Since the Mets needed players, several older players who were basically finished got one more chance to be regulars. Our player was one of those expansion regulars, and he had a very good season. For the first time in many years, he could think of himself as a star, although a very different kind of a star than he had been a decade earlier.

In the winter of 1962-63, however, Major League baseball re-defined its strike zone to help the pitchers, and this tossed many older hitters into a career-ending crisis. Our player was one of those. In 1963 Jerry Adair’s batting average dropped 46 points, Willie Davis 40 points, Bobby Del Greco’s batting average dropped 42 points, Norm Cash dropped 118 points, and our player dropped 52 points. This basically ended his career. Although he did receive a trial of a few games in 1964 to see whether he could regain his form, as most players do, he was released early in the 1964 season. He had a decent career, a modestly successful career, but blighted by that terrible injury that occurred early in the 1951 season.

It is a fictional career, and my main point is that the fiction is not external to the chart of numbers or built upon that chart of numbers, but rather that the fiction is told in numbers more clearly than it could be told in the same number of words. Numbers, like words, are capable of creating human images.

One of the first decisions you would have to make, if one were to create a fictional encyclopedia of baseball, is whether the fictional universe was embedded in the real history of baseball or was subject to its own rules. In this case I have inserted Player 1—we will give him a name in a moment--into the actual history of the game. This is reflected in his record probably in 50 different ways. This player played for Boston in the National League in 1947. The Boston Braves were an actual team, and they did move to Milwaukee in 1953, so the player moves with them. There was an actual expansion in 1962, which did in fact give many older players one last chance to play regularly, and many of those players did have decent seasons in 1962 but then had terrible seasons in 1963. Our player played 154 games in 1949 and 156 games in 1950. In fact, many players in that era did play that number of games; in that era teams played to a tie once or twice a year, and if a player played in every game that was usually 155 or 156 games.

But in creating a fictional encyclopedia of baseball, you don’t HAVE to follow those rules; you can make up a universe with its own rules. You can put teams in Buffalo and Indianapolis if you want to, and in Kansas City in the 1920s. You can have 8-team leagues or 12-team leagues; you can have 30 major league teams in 1947 if you want to. You don’t have to use a 154-game schedule up to 1962; you can use a 162-game schedule back in the 1930s, or you can use a 96-game schedule or a 180-game schedule or a 220-game schedule.

In real baseball the 1960s were a pitching-dominated era, but in fiction this does not have to be true; you can create .400 hitters in the 1960s and pitchers with 300 strikeouts in the 1930s. In real baseball there are very few relievers and just a handful of career relief pitchers before 1955, but in fiction this does not have to be true; you can have a pitcher who has a Goose Gossage type career from 1904 to 1920 if you want to.

In real life there are statistical standards that dominate each era of play. In the 1920s there were 89 regular players who hit for an average of .350 or higher, and seven who hit .400 or better, whereas in the 1980s there were only thirteen players who hit .350, and none at all who hit .400. In the 1980s there were six players who stole 100 bases in a season, whereas since 1990 no one has done that or even come close. In a fictional Encyclopedia one can follow those rules or ignore them and make up your own; it’s up to you. In the 1960s and 1970s there were many relief pitchers who pitched 75 games and 130 innings in a season, but that type of workload is entirely extinct in real baseball; in modern baseball no reliever pitches more than about 80 innings in a season. You can follow those rules, or you can decide that’s a stupid rule and baseball is more fun when relievers pitch like Dick Radatz did. If you want to you can make up a Jewish Encyclopedia in which everybody is named Samuelson or Meyer, or a Native American Encyclopedia in which everybody is named Pahmahmie or Wahquahboshkuk or Angry Bear.

What makes baseball records into words is the existence of statistical standards, or what we could call magic numbers. Players hit .300, or they drive in 100 runs, or get 200 hits, or have 40 saves. These are sometimes called magic numbers, although no one actually thinks that they are magical. The existence of the magic numbers makes all of the other numbers meaningful. The 100-RBI standard of excellence gives meaning to 90 RBI, or 80, or 70, or 110; all of the other numbers become something like words because of the existence of standards.

Generally, I prefer to make up some of my own rules, but if you get too far away from the rules of the actual major leagues, the fiction ceases to be interesting, because the standards don’t apply anymore. You can create a fictional universe in which players hit 110 home runs a season and drive in 400 runs a year, but it isn’t interesting because we can’t relate to it; the players lack not merely verisimilitude but in a practical sense they lack dimensions. They are off the grid; they are irrelevant to us. So generally, you have to follow at least some of the rules which have defined the real baseball universe over the years. But on the other hand, you can’t insert a player too deeply into baseball history, either, or he displaces the players who are already there. If you make this player the first baseman for the New York Mets in 1962, which I did, then he displaces Marv Throneberry, who was the actual first baseman for the 1962 Mets. That causes problems, too.

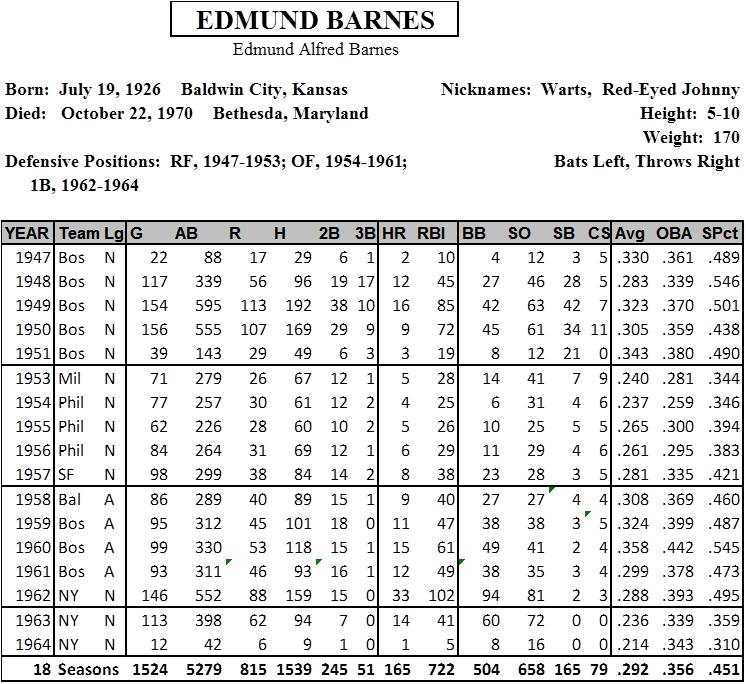

Now, Player One needs a name, and by the rules of Baseball Encyclopedias he is entitled to a little bit of biographical information—a date of birth, and a date of death, and a place of birth, and a nickname, a defensive position, and a note about whether he bats right-handed or left-handed. The second page of the handout gives the player all of these things. This has rules, too; for example, you can’t name a player "Kevin" or "Jeremy" if he played in the 1930s, because there were no Kevins and Jeremies who played in the 1930s. If you are a serious enough baseball fan it will be obvious to you that Player One was a left-handed hitter and was an outfielder, and also he cannot be 6-foot-3 and weigh 220 pounds because there were no fast-running outfielders in that era who were 6-foot-3 and weighed 220 pounds.

At this point we add the biographic information, and Player A becomes Edmund Barnes, who is on the back of the page:

Once you assign a player a name and a few biographical details, the player starts to merge into the world at large. If this player was born in 1926, then it is likely that he saw action at the end of World War II, although we don’t know that for sure. The fact that he died in Bethesda, Maryland, certainly suggests that he saw military service at some time, either in World War II or in the 1951-1952 period which is missing from his career register.

At this point I have a confession to make. Since I was twelve years old I have obsessively created what I think of as mythical careers for imaginary baseball players, which we will call for today’s purposes Fictional careers. I create them every day; I am not saying that I never, ever miss a day, but there won’t be 15 days in a year that I don’t do it. I have been doing this for more than a half a century. I have invented hundreds of different ways to create fictional careers for baseball players. In real life there have been about 18,000 men who have played major league baseball; that is, there are about 18,000 men who have played at least one game of major league baseball, although about half of those had just very brief careers. I don’t have any idea how many fictional careers I have created in my lifetime, but it certainly is many more than 18,000. I suspect that I may have spent as many hours creating these fictional careers as I have spent doing actual work related to my career. Most of those fictional careers no longer exist; they were created on computers which have long since died, or were written in spiral notebooks which have long since been thrown away or on note cards which have been lost.

As many of you know, Jack Kerouac had a very similar obsession, and I have met at least two younger people, both of them very successful writers, who confessed to doing the same thing, although I can’t share their names with you because they are public people and I don’t know that they want this information to be on the record. I don’t actually know why I am compelled to do this. I know that every day, when my mind gets jumbled up and my thoughts get tied in a knot, I switch over to Excel and create a couple of fictional players as a way of letting off steam. Some of my ways of creating these fictions are very quick; others are tremendously slow. Sometimes I will work for a week at creating a fictional baseball player, only to realize as I reach the solution to the puzzle that I have made some very basic mistake hours earlier or days earlier so that the player’s career turns out to be a mess that doesn’t resemble anything an actual career could be. It is like a soufflé that doesn’t rise or a desert that doesn’t jell; the resulting player’s career does not meet the basic conditions of the exercise, and so the effort does not scratch that itch that I am perpetually trying to satisfy, whatever that is. I don’t have any interest in superhero movies and am completely bored by them, but I suspect that what I get out of this stuff may be similar to what others get out of superhero movies.

I do feel guilty about the many thousands of hours that I have spent doing this, but I will also note that doing this has occasionally yielded professional benefits for me. I do in fact design and publish real-life record books for baseball players, and have done real encyclopedias; knowing how to do that is related to doing this. One of the happy accidents of my career is that I used to create projected records for players. . . in other words, a record showing what Lorenzo Cain will do in 2016. Whereas I think of most of what I do as a kind of scientific undertaking, I thought of THAT as just messing around, a part of my obsession more than a part of my work. But when I was pushed (against my will) to actually publish those projections, we discovered to my surprise that there was substantial public interest in them, and other people almost immediately started publishing their own projections to compete with mine. That was 30 years ago, and every real major league baseball team now uses projections of one kind or another to try to see what their team will look like before the season. When you think about it. . .well, of course they do; how can you do any kind of planning or detailed preparation for the season if you don’t have some idea of what it is that you expect each player to do?

Creating fictional careers requires a detailed understanding of the shape of actual careers. You have to understand what normal ratios are. You can’t give a player 86 games played and 416 at bats, because that isn’t a normal ratio, although there were some players in the 19th century who had ratios like that. You can create a player who doesn’t reach his peak until he is 32 years old and then is good until he is 36, but you have to understand how tremendously unusual that is. Probably the last star player who didn’t reach his prime until he was 32 years old was Mike Cuellar, forty-some years ago, although if I were to publish that fact no doubt the readers would turn up somebody else.

Anyway, for many years I had the dream of creating a fictional baseball encyclopedia by taking a couple of thousand of these fictional careers, or more, and blending them into a complex but somehow unified narrative. If you think about a real baseball encyclopedia, holding inside of itself 15,000 careers or thereabouts, every player is connected to every other player in there, and there are never seven degrees of separation in baseball; there are usually just one or two. You can pick any two players at random, and if you know the history of baseball well enough you can very quickly find a pathway between the two players, and also you can find the things that unify those two players. There are always things. Ty Cobb and Henry Aaron. One man—Fred Haney—was a teammate of Ty Cobb and a manager of Henry Aaron. Cobb and Aaron were from the same part of the country, separated by just about 300 miles. It can be shown that they played in many of the same parks, major league parks and minor league parks, and, of course, Cobb was a racist, while Aaron was a victim of racism.

Well, apply that to a fictional encyclopedia of 10,000 players. Do you see the possibilities? Suppose that there was a team that had two supremely talented players, like Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig, but suppose that something always went wrong for that team so that, despite having these two players together for ten years, they never are able to win the pennant. You don’t TELL that story; you create that story and put it inside the Encyclopedia, so that the reader, if he spends enough time with the book, will eventually discover it. Or suppose that there is the opposite; suppose there is a team of players of modest skills, a team that normally finished fifth or sixth in an eight-team league, but suppose that they have one really good player, and suppose that that one star player dies tragically early in the 1964 season, and then almost every player on the team has his best season in 1964 and they win 107 games and win the World Series as a kind of tribute to the teammate they have lost. Suppose that there are two sets of twins, brothers, and that in one set of twins one is the shortstop for the Brooklyn Dodgers while the other is the second baseman for the Yankees, and in the other set one is the second baseman for the Dodgers and the other is the shortstop for the Yankees. You don’t TELL that story; you create that story and put it inside the Encyclopedia, so that the reader, if he spends enough time with the book, will eventually discover it.

You’re not exactly hiding the story in the Encyclopedia; "hiding" suggests that you are taking active steps to cover it up. We’re not covering up the story; we are just creating the story and leaving it in there to be discovered by whoever is interested enough to discover it. The nature of it being an Encyclopedia will effectively hide the story. The unique nature of a Baseball Encyclopedia is that each player’s record is a story, but also each player’s record contains little directional arrows pointing you in a dozen different directions. You can’t complete ANY player’s record without studying the records of his teams and the records of his teammates, which means that you can never really fully process any player’s record. When you create a player’s record, it is easy to leave little clues as to whether the player is black or white, and because that is true in a fictional encyclopedia one could create the story of a team torn apart by racial animosity; one could create that story entirely out of numbers and biographical details, and then scatter the little pieces of the story across a two-thousand page book so that it might be years before anyone would discover that the story was there. Finding those stories is like finding buried treasure.

As a part of this exercise I have created a little 20-player Encyclopedia. I only have a few copies of that, for obvious reasons, but I expect to be able to post it somewhere so you can go online and download the Encyclopedia sample later if you are interested in doing that. Speaking of which, as I am writing this I really have no idea whether most of you understand what I am saying and are interested in it or not, but I know that in this audience there will be SOME people who love Baseball Encyclopedias and love spending time with them, discovering the stories that are hidden there, and I know that those people at least will understand exactly what I am saying and will get the idea.

Unfortunately, I believe that the time has come and gone when this fictional Encyclopedia of baseball could have been created and marketed. It’s a derivative effort, its appeal derived from and limited to the appeal of actual baseball encyclopedias. Baseball Encyclopedias are basically dead in print form now; their heyday was from 1969 to 1995. An Encyclopedia has to run a couple of thousand pages or more, and those books are expensive to print and expensive to distribute and sell, and there’s no real market for them in the modern world; online Encyclopedias can expand to contain more information in a better form, tied together better. The book I have been describing here could have been created and marketed in the 1980s, I think, but, like relievers who pitch 130 innings in a season, that day has come and gone.

The value in what I am talking about, I think, is not in what could be done, but that it pushes us to think about "What is fiction?" Good fiction, great fiction has psychological depth, it has imagery, it has cultural resonance. Good fiction creates a world and draws the reader into that world, where the reader may feel regret, terror, anxiety, hope, exhilaration and relief within the pages of words. Bad fiction is simply made up stuff. I am not arguing that fiction created with numbers could do ALL of those things that good fiction does; I am arguing that it could do some of those things very successfully. It could create a world of imagination, in which certain stories, which I acknowledge are stories of limited depth and power but which are stories of almost infinite variety, can be told. There is some difference between fiction and a lie. There is some difference between fiction and imagination; there is some difference between fiction and fantasy, but what is it exactly? Should this really be described as fiction, or does fiction have to rise to some level of sophistication which could never be reached in this format? I thank you all for your time and attention, and I will be happy to answer any questions you might have, whether about this paper or about other issues. But don’t ask me anything about Jack Kerouac, because I’m pretty sure you all know more about him than I do.