I’ve made a new friend in the past year, which is rare enough, and I’ve discovered that in his time he’s been acquainted with several MLB players, a couple of whom I’ll mention here. I thought I’d document a story that brings me within two degrees of separation, and maybe less than that, from some of my personal heroes. My newest friend, a gentleman named Joseph Stern, who turns 94 years old this Saturday, served in the Army Air Corps as a pilot during World War II. Now living year-round in Delray Beach, Florida, where I’ve recently bought a vacation home, Joe is a very modest sort of man, so it took several conversations around the pool for me even to understand that I was talking with a fellow who once had lunch with Ted Williams.

That’s the baseball takeaway of this article, by the way, so if you’re looking for sabermetric analysis this time around, this is about it: Ted Williams was witnessed eating lunch one day in March of 1944. That was about halfway through Joe’s service during the war, when he was a pilot stationed a few hundred miles northwest of Delray Beach, at Tyndall Field in Panama City, Florida. At the time, Ted Williams, still a Naval aviation cadet, was stationed at Bronson Field, in the Pensacola Naval Air Station, where he somehow made the roster of the camp’s baseball team. The Bronson Bombers flew 100 miles that March day to play a game against Tyndall Field. Williams’ Bombers, with three other major leaguers on it (one of whom was also Williams’ flying instructor), won that game, if you’re hanging in suspense.

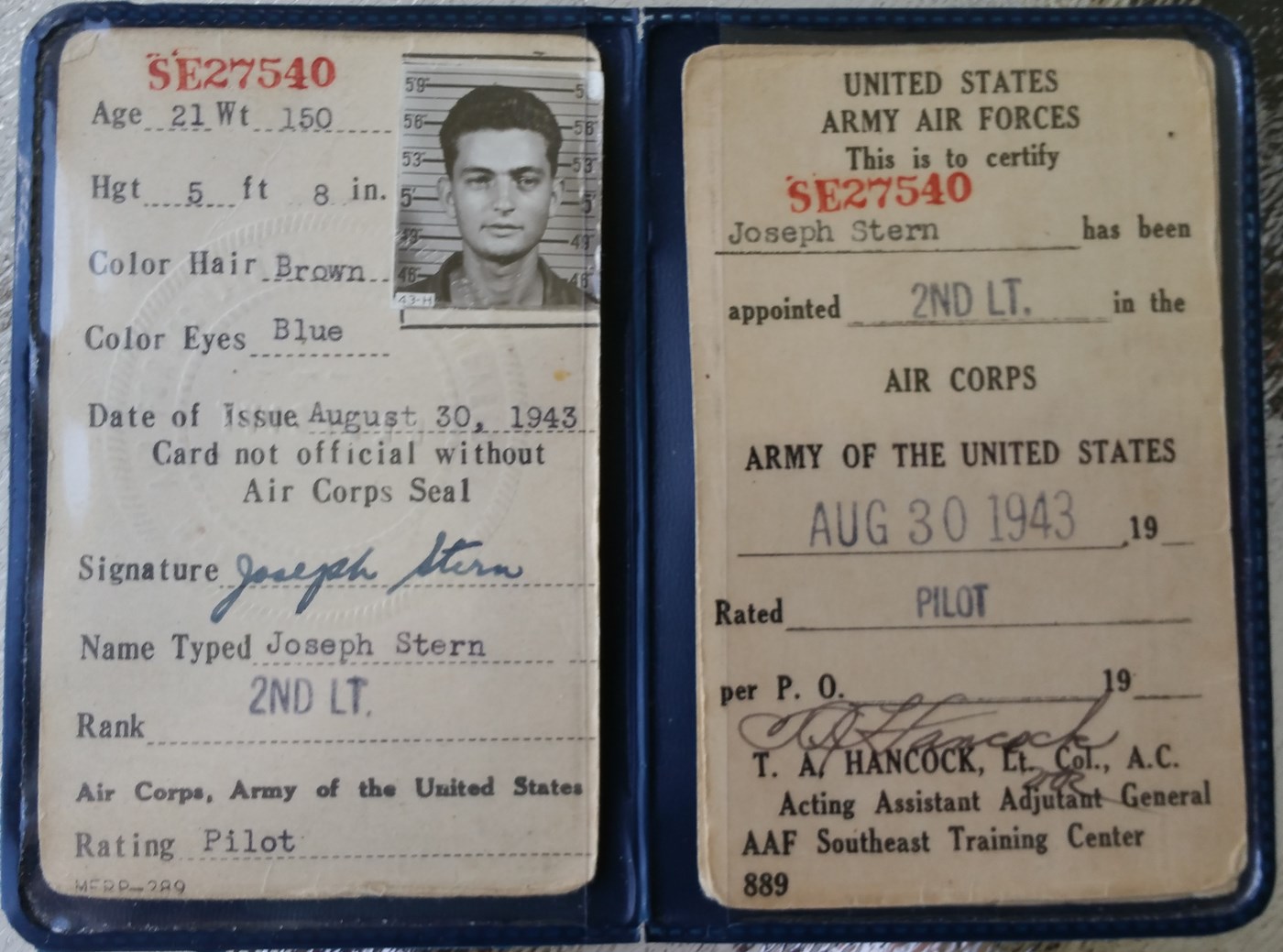

Listening to Joe’s detailed account of his service, buttressed with photos, documents, and Joe’s daily log of every plane he took up and landed (one day, a personal record of 23 take-offs and landings), I was most surprised by the hours and days and months of training he received before being certified as a pilot. Joe enlisted on October 31, 1942, and graduated from advanced flying school on August 30, 1943, getting intense training as a pilot at several air bases throughout the south during those ten months. There were many chances to wash out of the pilot training program, and most of those who began training with Joe did, in fact, wash out. Joe himself came very close on a few occasions, the closest call being in Mississippi when the director of pilot-training told Joe that his flying had recently gotten shaky. "It looks like you’re just afraid to fly," the officer suggested. "Let’s make it easy: I’ll write down ‘fear of flying’ and it will be over. Unless you’d like to quit?" Knowing he wasn’t the least bit afraid to fly, Joe very emphatically refused to drop out voluntarily. He enjoyed flying. But lately the Mississippi mosquitoes, he explained to me, mistaking him for a midnight snack, had kept him up at night. The constant drowsiness, not fear, affected his ability to land the planes smoothly, the most crucial part of a successful flight. Failure to land smoothly was the primary cause of other trainees washing out of the pilot-training program.

Landing was so hard, Joe explained, because the idea was to reduce speed as the plane approached the ground, but at the same time to avoid at all costs having the engine stall out before the plane’s wheels touched down. So coordinating all these factors perfectly—the plane’s speed, the alignment of the wheels and the landing gear, the nearness of the ground, the fuel feeding the engine—was the hardest part, and it was especially hard for Joe, as sleepy as he felt since arriving in western Mississippi. Even more than the sleep-deprivation itself, though, was its effect on his attitude, which was both irritable and a little sorry for himself. But he didn’t say a word of this to the officer questioning his courage that day. He just asked for a "check ride" with that skeptical officer, took off with him afternoon in a BT-13 plane, and, concentrating as hard he knew how, made a flawless landing. Joe stayed in the pilot-training program.

From a very early age, Joe had flying ambitions. Before he was enrolled in public school, Joe’s mother took him out to a street-corner in Brooklyn to see a parade honoring Charles Lindbergh, who had just returned from his solo flight across the Atlantic Ocean. Between Joe and me, we figured out that this parade took place a day or two after Lindbergh’s similar parade down Manhattan’s Canyon of Heroes, around June 12th 1927, two weeks past Joe’s fifth birthday. Lindbergh sat high in a big touring car riding the wrong way down Eastern Parkway, a mile or so from Ebbets Field, and Joe remembers Lindbergh wearing a grave expression on his face. But when he caught sight of the five-year-old waving at him, he broke into a warm smile. The two maintained eye contact for a few seconds, and Joe came away wishing he could be like the heroic figure in the touring car, without really understanding what it was a pilot did, or how he did it. Looking Lindbergh in the eye, for only a few seconds, had a powerful effect on Joe’s career choice.

Since talking to Joe, and writing the bulk of this article, I’ve done a little research, mostly reading Bill Nowlin’s thorough account entitled Ted Williams at War (published by Rounder Books in 2007, from which the photos of Williams and his teammates and of Williams at Pensacola Naval Air Station around this time were taken), which led me to the coincidence of Williams also being inspired by seeing Lindbergh, around the same time that Joe did, on the other coast:

Teddy Williams was almost nine years old, and Lucky Lindy’s flight started in his hometown [of San Diego]. It was no wonder that Lindbergh was the young boy’s hero. Ted has said that his earliest hero was indeed Lindbergh, and not any baseball player.

Ted had seen Lindbergh at the stadium one time when he was quite young. It was, he recalled, the day Teddy got his first barbershop haircut. [p. 53]

Joe had no idea that the young Williams (about three years older than Joe) had also seen Lindbergh. Despite his youthful dreams, airplanes were scarce in Joe’s neighborhood of Brooklyn, and it wasn’t until after Pearl Harbor, when he was nineteen, that he got to enlist in the Army with the intention of serving in the Army Air Corps. (The Air Force didn’t branch off into a separate arm of the military until the war was over. Williams, by the way, had all his flight training as a Naval aviation cadet, and didn’t get certified as a pilot, nor accepted into the Marine Corps, until about six weeks after Joe saw him play ball in March of 1944.) A highly detailed incremental process, pilot training required five stints of about two months apiece, beginning at an Army classification center in Nashville, where Joe was encouraged to train as a navigator. (Joe later learned that his IQ-test performance qualified him for navigator-training, which demanded a higher IQ-test score than pilot-training did.) "No, I want to fly," Joe insisted, so he was assigned in early 1943 to Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama, for preflight school, which Joe remembers mostly as a place of unpleasant drilling and hazing: "It was modeled on West Point, I think, the cadet system, and they tried to break you down so they could build you up again," he told me. "Upper-classmen, guys who’d been there only a few weeks longer than I’d been, would give you all sorts of silly orders, make you memorize nonsense and then recite it back to them, that sort of thing, just to teach you to obey orders without thinking about it. It was very childish stuff."

After preflight training, he was assigned to primary training school in Jackson, Mississippi, where he mastered solo flight, and next assigned to basic flying school in Greenville, Mississippi, where he had the run-in with the mosquitoes. Finally he was sent to at Stuttgart, Arkansas for advanced flying school. All in all, he had ten months of training, which I suppose isn’t very much considering that he had never flown a plane before enlisting, and after the ten months of instruction, he was an officer in command of his own plane. I was surprised to learn that by the middle of the war, training to become a pilot (and therefore an officer) didn’t yet require a college degree, which neither Joe nor Ted Williams had, since flying took not only physical qualities but also a good deal of training in advanced mathematics, which is not typically on high-school curricula. Cadets lacking college math and physics courses, like Joe and Ted, were at a real disadvantage in their training, but a few, like Joe and Ted, overcame that disadvantage: "Ted went through the training like a dose of salts," said Johnny Pesky, who was with his teammate in training school, according to Nowlin’s book [p. 38]. "He mastered intricate problems in fifteen minutes which took the average cadet an hour, and half the other cadets were college graduates."

I was also surprised to learn that, as soon as he was certified as a pilot on August 30, 1943, Joe wasn’t immediately assigned to fly a plane in combat. After all, the U.S. was at war and desperately training its young men for this exact purpose. But, in fact, Joe never flew a minute of combat, though the war would go on for almost two more years. He was assigned to Tyndall Field in Panama City, where gunners were being trained to shoot down enemy aircraft, and someone had to fly the planes that these gunners practiced shooting down. (Their guns aimed at their own planes were, of course, loaded with film, not bullets, the resulting photographs showing how precise their aim was.) This seemed, to me, at first, a shameful waste of all of Joe’s rigorous training, until I realized that expert gunners are needed no less badly than expert pilots as skilled in evasive tactics as the German and the Japanese pilots the gunners would be shooting at. So for most of the next two years, that’s what Joe did, first on big planes that simulated bombers, and finally on one-man fighter planes.

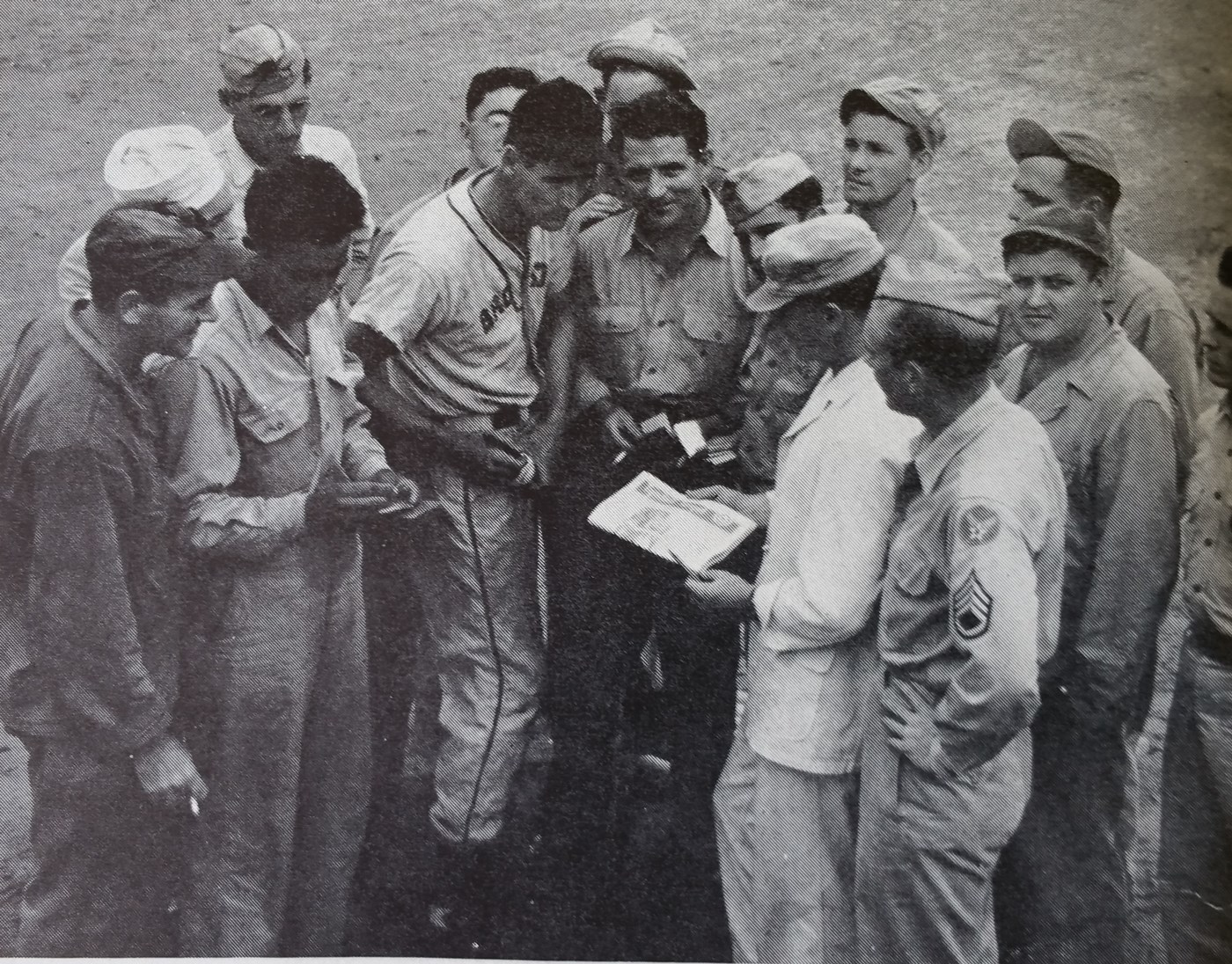

So Joe had been a second lieutenant assigned to Tyndall Field for about six months, when one day in March of 1944, Ted Williams arrived to play in a baseball game between Tyndall and Pensacola. Arriving in their white Navy uniforms, the Bronson Bombers changed into their baseball unis soon after landing in Panama City. Joe first saw him on the field, wearing his baseball uniform, signing autographs for a group of GIs. The baseball teams consisted of both officers and enlisted men, but Joe remembers thinking that it felt wrong to bother a fellow officer for his autograph. Like Lindbergh, Williams briefly made some friendly eye-contact with Joe, standing on the sidelines, but Joe declined to approach him, and the other officers present seemed to agree with Joe’s instinct: autographs were for GIs, not officers. Joe watched the whole game standing in foul territory.

Branson Field won the game, unsurprisingly, by the surprisingly close score of 5-3 (as best as Joe can remember, 74 years after the fact). Joe does remember quite clearly Williams’ at-bats, though: he hit two triples over the centerfielder’s head, both of which could have gone for four bases but for Williams’ stopping at third base. Williams also struck out once-- Joe recalls that all three strikes were swings and misses, which was a little unusual for Williams, I’d suspect. Probably someone can look this up, but on those rare occasions that Williams struck out, I would have thought most of the strikes would be "looking" rather than "swinging," a natural cost of Williams’ taking close pitches, but this (as well as airplanes and military service in general) may well be an subject on which I hold opinions supported by very little first-hand knowledge.

Who was the pitcher who struck out Ted Williams in a game where he was presumably trying his best to hit the ball? Wouldn’t that be a great story for that pitcher to tell for decades to come, even given Williams’ two monster blasts to deep centerfield? But Joe couldn’t supply the name of the man who achieved this feat, except that he, like all his teammates, never played major-league ball, as far as Joe can tell. (Nowlin tells the story of a Navy pitcher named Pat McGlothlin who held Williams hitless, 0-for-7, in a 19-inning game a few months afterwards. McGlothlin won one MLB game for Brooklyn in 1949, when the Dodgers won the NL pennant by one game.)

One of Williams’ Bronson Bombers teammates who had played MLB (and who taught Williams how to fly) was a third baseman for the Chicago White Sox named Bob Kennedy, Kennedy had already played parts of four seasons with the White Sox, peaking at 154 games for them in 1941. After the game was over, and the players had changed back into their naval uniforms, Kennedy and Williams appeared in the Officers’ Club to have their lunch.

For the only time Joe can recall, a "RESERVED" sign had been placed on a table in the Officers’ Club dining room, and Williams and Kennedy headed straight for that table. On the way there, however, Williams did pause at the table Joe was seated at, and shook his hand, without saying a word to him, and sat down at the table that had been reserved for him and Kennedy. Normally, each table seated four officers, but no other officers joined Williams and Kennedy (whose teammates were presumably all enlisted men), and no one even approached them for a conversation as brief as "Nice game, Ted." They simply let the two Naval officers eat their lunches in peace, and Williams and Kennedy made no effort to socialize with their Army counterparts, though they kept up a conversation between themselves throughout the whole meal. Joe was eating at the next table with three of his fellow pilots. The two major leaguers left the Officers’ Club and flew back to their Pensacola base after lunch. (Joe can’t remember what food was served that day, though he did remember that Southern-fried chicken was often on the menu, and quite tasty, usually accompanied by mashed potatoes and served with coffee out of a gigantic urn.)

Joe served as a target for the Army’s gunners-in-training for another year, when he was reassigned to Bradley Air Field in Connecticut to begin training for operational flying, switching around this time from P-40 and P-63 fighter planes to flying the P-47N. In the early summer of 1945, now assigned to Wilmington, North Carolina, he was notified that he and several other pilots were being re-assigned to fly combat missions in the Pacific Theater of War. Just before the unit would be shipped out to the West Coast in preparation for their postings on Okinawa, Joe’s girlfriend, Pearl, came down to Wilmington from Brooklyn to celebrate her 20th birthday on July 31, 1945, and to say goodbye to him.

That summer, Okinawa was occupied by U.S. troops but there were still several hundred Japanese soldiers secreted away in the mountains of that volcanic island. As if combat flying weren’t dangerous enough, Joe had also been warned in his training that these Japanese soldiers would often infiltrate the perimeter of the U.S. base at night, looking to slit the throats of American servicemen sleeping in their tents, succeeding at it at the rate of about one American soldier per night. When he bid Pearl goodbye, they both understood there was a very real chance they would never see each other again.

But this story, as you probably can guess, has a happy ending. As Joe was preparing to leave Wilmington in early August of 1945, the news arrived about Hiroshima and, a few days later, about Nagasaki. Joe’s orders were immediately cancelled, and in fact he was out of the service by early fall. He and Pearl got married ("Mostly happily," says Joe, "though that’s a whole other story") and stayed married until 2012, when Pearl passed away. After a career running a machine-parts business in Brooklyn, while continuing to serve in the reserves through the 1950s, Joe retired with Pearl to Delray Beach, where he now lives (as his fellow Brooklynite Walt Whitman put it) "healthy, free, with the world before me" at the age of 94. I usually see him at the pool in the late afternoons, where he and I enjoy a swim when I’m down in Florida. Every Saturday, he and another friend of his enjoy a spirited discussion, often political, sometimes heated, always friendly, over breakfast and then around the pool, where he does a fine job upholding an informed liberal perspective on issues that his friend often dissents from. With his good health, with his sharp memories, with his friends and devoted family, Joe’s a pretty lucky fellow in my book. I’m sure he joins me in wishing all of you a happy and peaceful Memorial Day.