2017-57

The Note

Handwriting expertise, more clearly than any other field that I know of, illustrates the difference between science and expertise. Science uses general rules and principles, understood by millions of people, to work toward increasing our shared understanding of the world in which we live, a key word being "shared". What is learned by the scientist is in no sense the property of the scientist, if it is truly science and not commerce. If in our field we were to discover, for example, that tall hitters do best against tall pitchers and short hitters do best against short pitchers, the value in this would not be to me, but to a baseball team by way of its manager. The manager would be as much the owner of this knowledge as the analyst who discovered it. Crucial to that fact—to the shared nature of its ownership—is how it is known. If I were to say that I know that tall hitters hit best against tall pitchers and you should believe me because I am an expert in this field, no one would believe me and no one should believe me. Others would believe me only if (1) I were to present evidence demonstrating that it is true, and then only if (2) others were able to study the same subject and reach the same conclusion. Studying the same subject and reaching the same conclusion or a different conclusion does not require expertise limited to a small cadre of persons; it merely requires that we apply the rules of scientific enquiry which are universally owned and widely understood. Shared principles yield shared knowledge.

Expertise, on the other hand, is the property of the expert. The only way that WE know that Document 1 and Document 2 were or were not written by the same person is that an expert says so. The only way to get a second opinion is to ask another expert. If the other expert cannot get access to the documents, you can’t get another opinion.

A couple of years ago here I wrote something about the handwriting in the Zodiac case; the Zodiac wrote several letters which were mailed to newspapers, and there are disputes about which are legitimate Zodiac letters and which are not. I argued that something which was allegedly said by an expert handwriting analyst could not possibly be true. The reaction of some of you, some readers, was "Why should we believe you, rather than the expert? You’re not an expert."

Of course scientists acquire expertise in science, just as mechanics acquire expertise about engines, ditch diggers acquire expertise about shovels, and bartenders acquire expertise about the behavior of persons under the influence of alcohol. Scientists sometimes move into being experts in the same way that comedians move into being actors. The law confuses the issue, and the legal profession confuses the public, by using scientists as experts. But science and expertise are natural enemies. Expertise is based on credentials, experience and on trust. A scientist is trained NOT to trust, and knows not to be in awe of credentials. The most highly credentialed scientists in the world in our generation will be proven in the next generation to have been dead wrong about major tenets of their work.

Handwriting, on the other hand, has NO field of free-standing knowledge open to the public and verifiable by the public. It could have; it should have. It just doesn’t. Handwriting analysis perfectly well COULD be done by scientific methods; it just isn’t. The field went in a different direction. It developed expertise independent of verifiable knowledge.

I should say . . ."handwriting identification" has evolved into "document examination" or some similar phrase, document verification. Document examination is a more scientific field than handwriting evaluation, relies more on modern science. Document examiners study things like the ink and the paper and the soil residues on the paper, and generally have more of a grounding in scientific methods.

Anyway, my view is, no one has to be an expert to speak the truth. If I say something which is true and which you can verify as being true through your own observation, why do I have to be an expert to say that? That makes no sense to me. The experts have seized control of the discussion, so much so that no one else is allowed to speak, even to speak the truth.

With that preamble, I’ve been looking in the last week at the handwriting in the JonBenet Ramsey case, which is not cursive writing but printing. I had never really studied it before. I had read about the handwriting in the case that there were many similarities between the handwriting of the ransom note and the independently known samples of Patsy Ramsey’s handwriting, but that no expert will testify that she wrote the note. Steve Thomas, the detective who wrote a book about the case, tries to create the impression that Patsy probably DID write the ransom note; all the experts agree there are many similarities between the handwriting of the note and Patsy’s handwriting, but they just unfortunately were never able to get an expert to cross that little bridge between saying there were many similarities in their handwriting, and saying that she actually wrote the note.

Also, it is speculated in different places that the writer of the ransom note could have been attempting to copy Patsy’s style or to fake Patsy’s handwriting.

This was all I knew about the handwriting in that case until the last couple of weeks; I just accepted that the handwriting was somehow problematic for Patsy’s defenders, and let it go at that. But in connection with another project I am working on, I had to get into the details.

Wow.

Patsy Ramsey did NOT write that note. It should be obvious to anyone who studies the subject that Patsy Ramsey did not write that note, for reasons that I will outline later in this article. No expert will EVER testify that Patsy Ramsey wrote that note, because if they did, they would be torn to shreds on cross-examination so completely that it would end their career, absolutely and beyond any question. It’s never going to happen.

Also, the perpetrator was NOT attempting to copy Patsy Ramsey’s handwriting. There are four documents relevant to this dispute which have worked their way into the public discussion, which are:

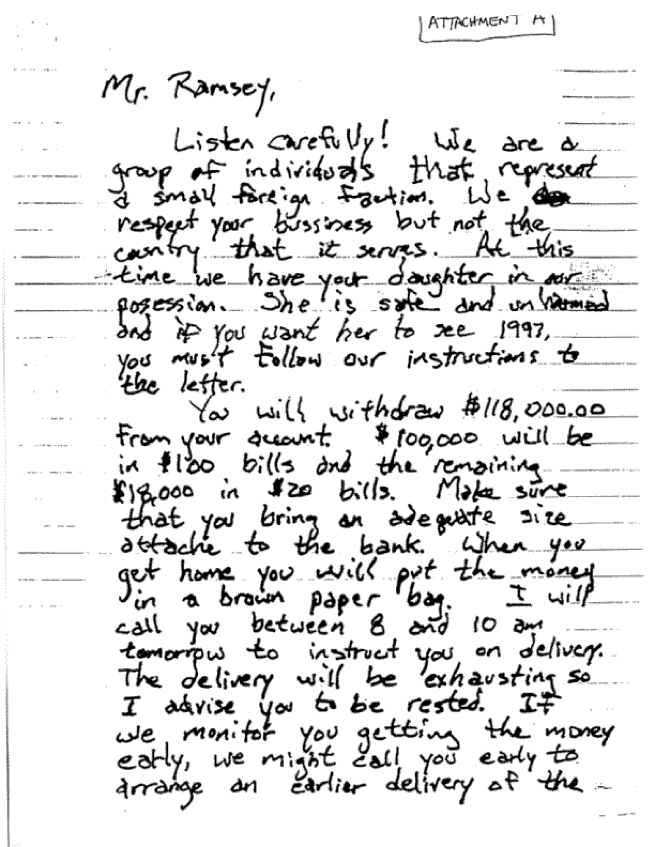

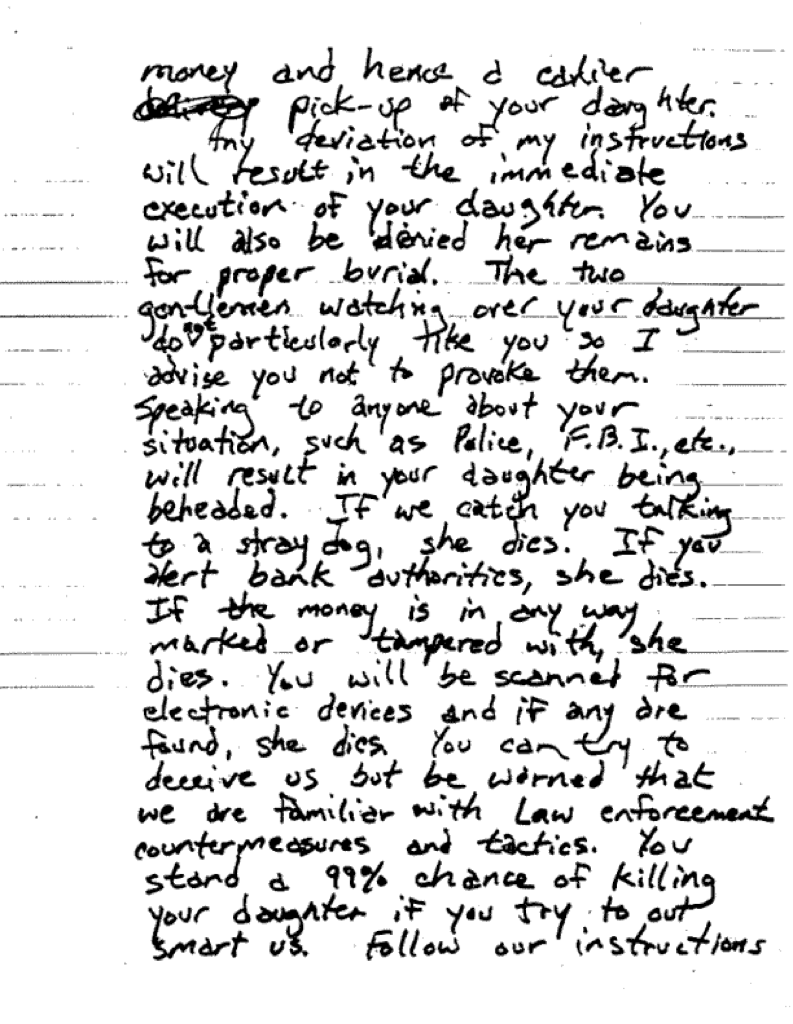

1) The Ransom note,

2) A letter that Patsy wrote before the murders, which is known as the London letter. The police came into possession of the London letter and used it as a basis of comparison of Patsy’s handwriting, and other documents as well, but these three documents listed here somehow leaked to the public.

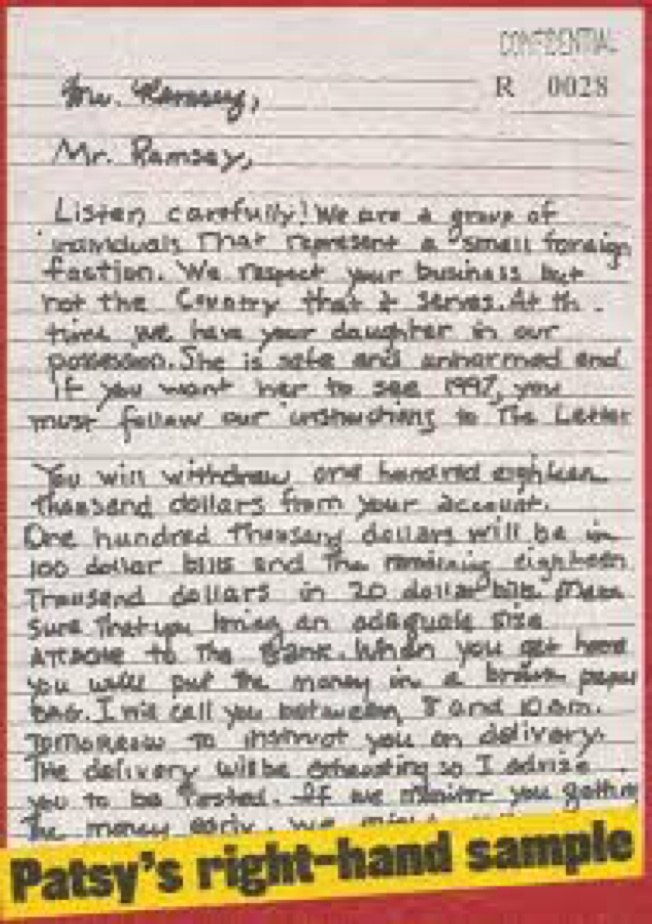

3) A page of Patsy’s copy of the ransom note, which will call the Copy letter. Police in a case like this will dictate to the suspect the words of the note and instruct the suspect to write them down. You may have seen the Alfred Hitchcock movie The Wrong Man, in which a man spends years in jail because, while doing this, he makes the same spelling error that a bank robber had made in writing his note to the teller, spelling "drawer" as "draw". There have also been several cases in which suspects were convicted after the police told them to misspell a word in a given way, and then later lost track of the fact that the suspect was instructed to spell the word that way.

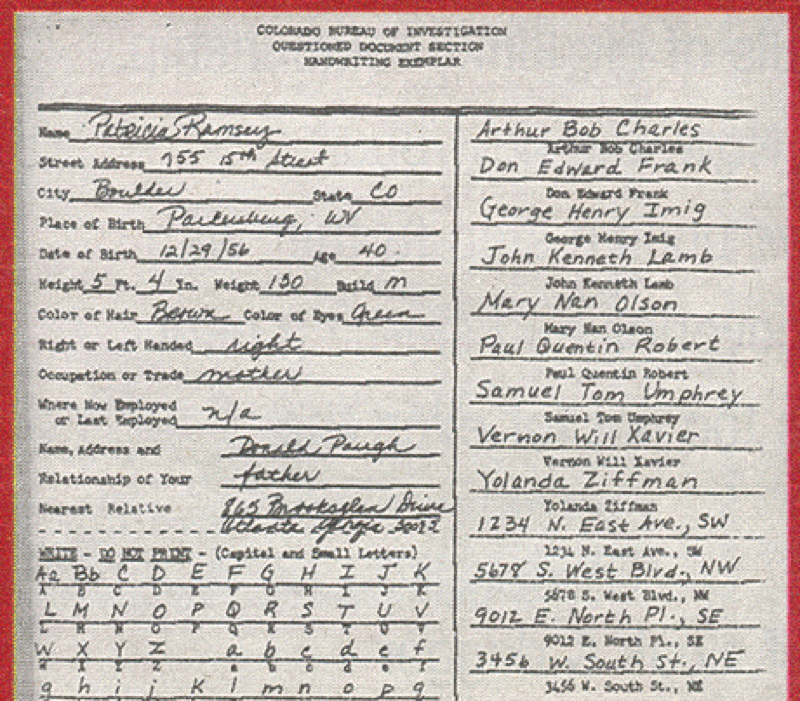

4) A handwriting exemplar taken of Patsy’s handwriting by the Colorado Bureau of Investigation.

To establish the basis of our discussion, here are photocopies of those four handwriting samples.

1. The Ransom Note

2. The London Letter

3. The Copy

4. The Exempler

Incidentally, if you get really into this subject I would recommend that you not go to the web site where you can find these things, as there are viruses lurking there.

Let me pause here to embrace a couple of principles espoused by handwriting experts. One thing that handwriting experts say often is that when dealing with a longer document, you ignore the first paragraph or the first couple of paragraphs, and focus on the later part of the document. A person writing a ransom note will often try to disguise his handwriting, but the efforts at disguise require so much concentration and effort that, after a few lines, the disguise efforts will break down and the person’s natural handwriting (or printing) will come through. I believe this to be true, and you can see in the ransom note that the writer did this; he or she did try to disguise their handwriting in the first few lines, but gave it up after a couple of paragraphs.

The second (related) thing the experts say is that it isn’t really possible to effectively disguise your handwriting, or not practically possible; you might be able to do it somewhat with a lot of practice and with more than a normal amount of time. I believe this to be true. In this case, for example, when Patsy Ramsey writes a small "v", she normally makes the two sides about equal, and makes the left half the highest stroke more than 60% of the time, whereas the person who writes the ransom note always or almost always makes the right side of the v higher than the left side, and usually MUCH higher. (In making a capital "V", Patsy makes the right half higher than the left.) Are you aware of whether you make the left or the right side of a "v" higher? Probably you aren’t—but if you check something you have printed, you will find that you have done one or the other. It is difficult to fake something like that, because when you print you are making 5 to 7 decisions per second about how to form the letters, and it just isn’t possible to remember to fake something 5 to 7 times a second. You’re not normally aware of the small details of how you form your own handwriting. If you try to make yourself aware of it, you can’t do stuff that fast. You can slow yourself down, but (a) you can’t slow yourself down ENOUGH, and (b) when you slow yourself down and deliberately change how you form the letters you are drawing the letters, rather than natural handwriting, and the difference is obvious. This is what the experts say, anyway, and I believe this to be true.

So getting to the subject. Patsy Ramsey and whoever wrote the note were taught the same style of handwriting; that is, they were taught by teachers who were trained in the same way. The similarities do not go beyond that. For example, in writing a capital "D", both will start the circular or elliptical stroke substantially to the left of the downstroke/left pole of the D (although even there, I think one could easily recognize whether the "D" was written by Patsy or the ransom letter writer.

But if we focus on a simple letter like a small "i"; there are four large differences in the way that Patsy makes an "i" and the way that the ransom writer makes an "i":

1) Patsy doesn’t put the dot on the i until after she has completed writing the word, which causes her to very frequently misplace the dot. Often the dot on her i is not over the i at all, but over the letter which is next to the i, to the right. As she finishes the word she goes back to dot the i, but she doesn’t move the pen back quite far enough, so the dot winds up over an n or an r or an s. In the ransom letter there is one case where the writer misplaces the dot, but that is one out of maybe a hundred small i's, whereas Patsy does it constantly. We’ll all do it once in a while.

2) The ransom writer will often move his pen as he applies the dot above the letter, creating a dot which is not really a dot, but more of a small slash. Patsy never does this; she taps the pen to the paper, creating a small, precise dot.

3) Referring to the parts of the letter i as the dot and the post, the ransom letter writer makes a very short post almost 100% of the time; in a couple of cases the post is just another dot, so that the letter i looks almost like a semi-colon. Patsy does not do this; in fact, her post is rather tall, taller than I would make it if I was writing.

4) The ransom writer often or usually curves the post so that it almost a c shape, the bottom of it curving to the right as if the writer was rushing to get on to the next letter. Patsy draws a very straight post, and usually slants the post with the bottom to the LEFT and the top to the right.

Patsy:

The ransom note:

Patsy picks up her pen much more often than the ransom writer. The ransom writer almost drags his pen from one letter to the next, even though he is printing. Patsy picks up her pen between letters. The ransom writer is rushing to get from one letter to the next, and does things which create a "half bridge" between the letters. The most obvious case in which he does this is the "n", small letter n:

The ransom letter writer draws his pen off to the right at the end of the "n", almost joining it to the next letter. Handwriting experts sometimes call that a "foot"; he creates a foot on the "n". He does this a high percentage of the time, and opens the n up at the bottom almost 100% of the time:

He does the same with his "h’s" and "m’s", less notably on the "m’s":

Patsy does not do that; she closes off the h, m, or n by drawing it back in the opposite direction—toward the left post of the n—in most cases; in some cases she finishes it straight down. The way she finishes an h, n or m is the OPPOSITE of the way the ransom letter writer finishes; she closes it off by moving her pen back to the left; he opens it up by moving his pen to the right. But this is not the largest difference between the two of them in their h’s, m’s and n’s. The LARGEST difference between them is that the ransom letter writer puts a "tent" at the top of his of h’s, m’s and n’s, almost a sharp point at the top of the letter. Look at the examples above; he does that in every case except the word "can’t". He’s very close to 100% in having a sharp turn at the apex of those letters.

Patsy, on the other hand, draws a very ROUND roof on her h’s, n’s and m’s—as different from the ransom letter writer as it could possibly be:

There are a couple of instances in which Patsy drags her "n" off to the right, although even in those cases it isn’t really like the way the ransom writer does it. I should stress, if I haven’t, that the way Patsy and the ransom letter writer were TAUGHT to construct letters, when they were 5-6-7-8 years old, is identical. They were taught by exactly the same method. There are some differences in what could be called the architectural structure of the letters, but more than 90% of it is the same. What is different—100% different—is the individual habits of the writers. That’s the stuff that can’t really be faked. You can’t "remember", every time you write an h or an m or an n, to put a "point" at the top of them, if you don’t normally and naturally put a point there.

Almost every letter of the alphabet has these kind of obvious interpretational differences. The ransom letter writer, in writing a "t":

1) Uses a DOWNWARD slanting crossbar more than 80% of the time,

2) Usually puts the crossbar comparatively LOW across the post, and

3) Usually curves the post with the bottom of the post curving to the right.

Patsy:

1) Uses an upward slanting crossbar,

2) Usually puts the crossbar higher up on the post, and

3) Usually makes a straight-line post, which normally leans to the right so that the bottom is to the LEFT, whereas in the ransom note it is toward the right.

These things can be seen in the examples I have already given, or here. Patsy:

In making the letter "o"—small o—the ransom letter writer often makes about ¾ or 4/5 of a circle and then finishes it off by drawing a line across the top, back to the starting point, making a flattop o or sometimes a round o. Look at the words "situation" above, and "southern" and "John" and "money"; you’ll see what I mean. Patsy, on the other hand, draws an oval-shaped o that finishes back where it starts, and sometimes over-traces part of the top of the o, moving her pen at the finish back over the start. Look at the words "London" and "hope" and "join" above.

In making a capital Y, Patsy makes three distinct strokes, drawing the Y with three lines, whereas the ransom letter writer makes a two-stroke Y; that is one of the few letters that is architecturally different between the two writers.

In making the letter "f", small f, there are. . .shoot, there must be a dozen differences between the two of them. Patsy uses a round "cap" on the f; the ransom letter writer uses a flat cap. Patsy makes the f with only two strokes—always—while the ransom letter writer makes the f with three distinct strokes—always. I don’t see any exceptions. Adding the crossbar, Patsy makes a flat line which is usually parallel to the line on the paper; the ransom writer is never parallel to the line. The ransom writer’s crossbar slants up or down depending on the next letter; if the next letter starts at a high point then he slants the crossbar up, leading into the next letter; if the next letter starts at a lower point then the crossbar slants down. Frequently, in drawing the crossbar both on the f and the t, the ransom letter writer makes a CURVING motion. Patsy uses a flat, direct motion. Also, in making the f, Patsy’s crossbar will extend out further to the right than the "cap" or "roof" of the f does, whereas the ransom letter writer almost always extends the top of the "f" further out to the right than the crossbar.

In making a "w", either a capital W or a small w, the ransom writer will either (1) make a "two-v" w or (2) bring his pen up so little at the bottom of the W that it is almost a wide "U" with just a small notch at the bottom. Patsy doesn’t do either of those things; she makes a "two-u" w with rounded bottoms. . . .consistent with her n’s, h’s and m’s; Patsy makes circular motions whereas the ransom writer often makes sharp turns in the middle of a letter. (Sometimes Patsy will use the double-v w, rather than the double-u w.)

Line orientation. . . .Patsy is an "above the line" writer. Most of her letters hover a fraction of an inch above the line, with only the letters that are supposed to drop down (g, j, p, q and y) dropping below the line. Other than those letters which are designed to drop below the line, less than 5% of her letters go below the line. The ransom writer, on the other hand, normally rests his letters ON the line, and actually drops below the line on MOST letters. I counted 126 letters from various points of the letter, of which 82, or 65%, actually go below the line at some point.

I wish I had looked into this years ago; it would have changed what I wrote in Popular Crime. The ransom letter writer absolutely was NOT copying or mimicking Patsy’s handwriting method; they were just taught to do things in the same way, so that there are occasional words that come out looking similar despite the massive differences between them.

Also, I had not "gotten" this before. There is a line in the ransom note that reads "you are not the only fat cat around, so don’t think that killing will be difficult." The line doesn’t make a lot of sense; why does the number of "fat cats" around have anything to do with how difficult it is to commit murder? The murderer clearly was acting out a fantasy of being a master criminal. There are a series of movies in which a nefarious actor seizes control of an innocent victim and uses that control to extort money from someone who has money, and the murderer clearly was clearly acting out a fantasy driven by those movies. What he seems to be saying is that he may use the murder of JonBenet as leverage in some FUTURE crime. He is threatening John Ramsey that he may kill JonBenet to prove to his NEXT victim that he will kill the person who has been kidnapped. (JonBenet was alive at the time the letter was written.)

This matters, because there is another crime that may or may not be related. That’s a tangent so I won’t follow it, but (while I generally do not think that the two crimes are related) this line seems to indicate that he may be planning a follow-up event.

Thanks for reading.