When I was getting my mind cranked up and caffeinated to write my previous piece, "How Sabermetrics Has Ruined Baseball," improvising the sort of stuff that usually (but not-this-time) gets red-penciled from the final product, I found myself describing the time I came within a whisker of batting against Tom Seaver. Wisely, I decided to take the piece in a different direction, but after "How Sabermetrics…" was published, I tested my memory by looking up exactly when this event took place (or almost took place). I found two archived articles delineating the event, and reminding me of all sorts of details that had slipped my mind:

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/09/14/sports/sports-world-specials-whiff-then-watch.html

http://metsguyinmichigan.blogspot.com/2009/05/baseball-spot-no-54-babe-ruth.html

As I noted in the "Comments" section of that "How Sabermetrics…" piece, I remembered the event pretty well, my only major lapse of memory being that I remembered it as being closed to the general public and open only to working journalists. I misremembered that part because part of the event was closed to the general public, and I got into that part with a certain amount of effrontery, pushiness, and perhaps charm. Mostly pushiness, I think.

I had called up the Museum’s PR person and requested a press pass for the Tom Seaver event, on the basis of a few pieces I had just written for the previous year’s (1986) Baseball Abstract, which, I informed her, made me a sports journalist. I had just moved to the Capital District, and was setting up shop as a freelance journalist for the time being—these baseball articles (really, just letters I wrote to Bill that he printed) were my bona fides.

My claims were true, as far as they went. I had very recently moved to the state capitol: my then-wife and I had closed on our new house in late August, and this phone call probably took place in very early September. She was a few days into her new job, directing the journalism program at SUNY-Albany, and I was a week or two into my new job as unemployed house-husband and full-time caretaker of our daughter, the same daughter whose birth the previous autumn Robert Coover had noted with an elaborate inscription of his Public Burning novel (a fabulous book, btw). Since she was born during the 1986 World Series, I had unsuccessfully argued that we ought to name her Mookie, but we ended up naming her Elizabeth Lee Goldleaf. If not for Elizabeth, I would certainly have batted against Seaver that day.

The day was a celebration of paintings about baseball, which were to be displayed at the State Museum in Albany. Seaver had a reputation as baseball’s cultural maven. The "Mets Guy in Michigan," a contributor BTW to a Mets website I’d started http://www.thecranepool.net/phpBB/ , writes that he’d "heard stories that Tom Seaver would often take young players under his wing, and take them to see art museums while on road trips." As the Mets Guy tells it, he read about the event, saw that his boyhood idol was going to appear (and pitch to 30 lucky lottery winners), but he found the drive from Connecticut too far for him to make that day. Since I was living right near the Museum, I had no such excuse, so I drove into town in hopes of meeting, and maybe facing, my boyhood idol that day.

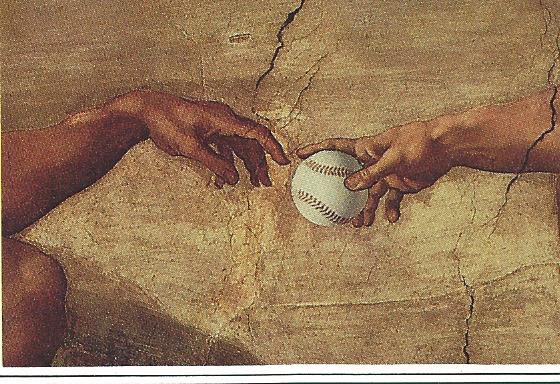

I got into the exhibit, entitled "Diamonds are Forever: Artists and Writers on Baseball," which featured 116 paintings, sculptures, and manuscripts by such artists as Andy Warhol (a portrait of Seaver) , Claes Oldenburg (''The Mitt")

, Claes Oldenburg (''The Mitt") , Michael Langenstein (a parody of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling)

, Michael Langenstein (a parody of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling) , and other luminaries of the art and literary worlds. I carried with me a 117th artwork (reproduced in the "How Sabermetrics…" article) that I had painted a decade earlier, hoping to get Seaver’s autograph on it—precisely, on the baseball that occupied the lower left-hand quadrant of the painting, the remainder of which happened to be of Seaver himself throwing that baseball. How could he refuse me, especially on this occasion commemorating baseball and art?

, and other luminaries of the art and literary worlds. I carried with me a 117th artwork (reproduced in the "How Sabermetrics…" article) that I had painted a decade earlier, hoping to get Seaver’s autograph on it—precisely, on the baseball that occupied the lower left-hand quadrant of the painting, the remainder of which happened to be of Seaver himself throwing that baseball. How could he refuse me, especially on this occasion commemorating baseball and art?

Turned out, he didn’t get the chance to refuse me at the journalists’ event, because I couldn’t elbow my way close enough to him to ask. First he was introduced, then he spoke for about fifteen minutes about the arts of pitching and painting, and then the floor was opened up to journalists’ questions. It hardly seemed appropriate to request an autograph in the Q and A session, so I decided to wait until afterwards.

Afterwards was worse. The reporters thronged around Seaver, introducing or re-introducing themselves to him, shouting more questions to him, some of which he deigned to answer, as he made his way to the room’s exit. Oh, well, I thought, I can catch him at the next event.

The next event, which followed the press conference immediately, was the public exhibition of pitching, and it took place in Lincoln Park, just outside the State Museum and right behind the Governor’s Mansion, then occupied by the first Governor Cuomo, a former farmhand in the Pittsburgh Pirates organization. Seaver stood on the pitching mound in the park, where the crowd that had come to see the great Seaver was issued tickets, the torn-off half of which went into a barrel. Thirty lucky observers would have their half-tickets fetched from the barrel, and these thirty lucky fellows would get to stand in the batter’s box facing the great man.

When I call him "the great Seaver" or "the great man," I’m being perfectly sincere—not only was he an icon of my youth, but I think, a little more objectively, that he was regarded, and still is, as one of the half-dozen greatest pitchers in baseball history. He still holds, as far as I know, the highest percentage of votes any first-ballot Hall of Famer has ever gotten and no one, I think, begrudges him that honor. His name must be mentioned when the subject of the Greatest Pitchers of All Time comes up: his name, Lefty Grove’s, Walter Johnson’s, Christy Mathewson’s, Roger Clemens’, and maybe one or three other contenders. You can’t omit Seaver from that conversation.

But I’m being a little sardonic, too, in that Seaver’s reputation is that he carries himself with the clear understanding of his place at the pinnacle of baseball success. He has no false modesty about his achievements, and not much real modesty either. Fans who have run into him, in public places like the elevator at Shea Stadium (the one that broadcasters, as Seaver was for a while, must ride with fans from time to time), have reported that their chance encounters with Seaver were more disheartening than anything else. Far from warm or friendly, Seaver would ignore such greetings as "Hey there, Tom" or such truncated impromptu speeches beginning "You meant so much to me growing up…" Instead he would routinely refuse to shake fans’ hands, or to autograph whatever they tried to push into his hands, or even to acknowledge their presence.

My own feeling is that he has every right to protect his privacy, and has no obligation to perform such rudimentary acts of generosity or good public relations as fans might wish. After the first few thousand such requests, it must get tiresome (hard as it may be for us to imagine) to be heaped with praise, with thanks, with blessings, even with awestruck silence. "Yeah, yeah, been there, heard that, bought the T-shirt," etc. Seaver has even been known to snap sarcastic or dismissive remarks at fans who step across the line of persistence.

Like I say, he’s under zero obligation to meet fans’ expectations. I’m merely noting that he sometimes chooses not to do so, and fans who report such tales often tell of similar encounters with other boyhood heroes that do not feature Seaver’s death-stare and withering remarks. More often than not, such other encounters are charming, even heart-warming, accounts of running into an idol and getting smiles, snippets of conversation, autographs aplenty, even thanks for remembering them so well, whereas with Seaver, the common response begins, "I was SO disappointed when I…." and plummets sharply downhill from there.

So I knew not to expect a lot of geniality from someone I had such genial memories of, but I also figured at an event open to the public, or the preceding one which he had opened up to questions from the press, I might luck out and get a response from him that I’d be pleased to get. Secretly, I was even hoping that he’d find my painting of him (the Cincinnati uniform clearly showed Seaver’s uni number, "41," on it) so charming, even so artistically distinguished, that I entertained thoughts of what I’d say if he offered to buy it from me on the spot. (I hadn’t yet sold a painting, so I was getting a lot of pleasure from that fantasy alone.) I and the other journalists joined the crowd, entering our tickets into the lottery of 30 lucky fans who would stand in the batter's box against the great man.

There were hundreds of fans there that afternoon, at least 200, maybe 500, so I understood what a longshot it was that my ticket would be selected. And apart from a parakeet in 1965 and a mini food-processor in 1997, I’ve never won any random drawing in my life.

But lo! my ticket was picked, along with 29 others.

We lucky 30 were delirious with joy, though I was immediately filled with anxiety. In short, I faced two very specific problems that no other winner faced.

Problem #1 was that I was carrying around that damned painting. I was loath to leave it on the ground while I batted, and I didn’t want to ask some stranger to guard it while I stood in against Seaver.

Problem #1 was nothing, though, compared to Problem #2.

Problem #2 was Daughter #1. Since I was tasked with taking care of her, I’d had to bring her along to the event. This whole while, in other words, I was carrying my painting in one hand (it’s not a miniature) while carting around a ten-month-old in a baby-carrier on my back.

I like to think I’m a sensible fellow. I like to think that, assessing my situation, knowing no one in the crowd (actually, aside from my wife and daughter and maybe the lawyer at our house-closing, I didn’t know anyone by name within 90 miles of Albany at the time), I would instantly reach the conclusion that, lucky though I be, this at-bat wasn’t going to happen.

If I couldn’t trust a stranger to watch my painting and if I couldn’t leave it sitting on the ground, then surely I couldn’t even consider doing either with my infant daughter.

Could I?

I am sorry to report that I gave both these options serious consideration before considering an even loopier option.

"Let’s see, if I place the baby-carrier on the ground," I thought, "right there, in the on-deck circle, I can keep an eye on it as I bat. But that’s kinda dangerously close to the field—an errant throw, or a foul tip, and the baby is at risk. But any further away, and then I can’t keep my eye on her. Wot a dilemma! Okay, maybe I can ask someone to watch her for a minute—surely I won’t last much longer than that, batting against Seaver. How about that guy? No, he looks a little too disreputable. That other guy looks more trustworthy—though for all I know, he’s a child-molester or a potential kidnapper. Even a killer, possibly. All of these strangers, honestly, look like convicted baby-abductors, or worse! No, my only choice is to enter the batter's box with Elizabeth Lee in the baby-carrier on my back. Yes, that’s the ticket."

I don’t know how long such thoughts flittered through my mind. I like to think myself, as I say, a sensible fellow, so I compliment my sound judgment by opining that this thought process lasted no more than an instant. But I can’t be sure. It’s just as likely that I’m such a senseless fellow-- an idiot, really-- that I actually stood there and entertained these possibilities for a full minute or two before accepting that I could not bat against Tom Seaver that afternoon.

I know I reached the turning point when I tried to picture myself batting with a baby on my back. As if I wouldn’t be overmatched enough against Tom Seaver! I tried to picture the bat curling around my back as I awaited his first pitch, and tried to gauge whether it would brush against the baby’s head. Then I tried to picture myself swinging at a Seaver pitch, and what would happen to my tiny passenger as I exerted maximum torque trying to get the bat to meet the ball. And what would happen when I missed (as I inevitably would)? What would happen on the backswing? Might I wallop my infant child with the hardest swing I’d ever swung with a 34-ounce bat?

I would honestly like to report that none of these thoughts entered my mind, but in the interest of journalistic integrity, I must report that all of them did.

Was this a response that only a fanatical baseball fan, fanatical Mets fan, fanatical Seaver fan would even let flutter through his mind? In my darker moments of self-reflection, I wonder if being any kind of fan is finally no excuse at all, and my response was simply that of a terrible father. In the least insane of the three insane options I considered in those few moments, asking a stranger to watch my baby, I would be violating a precept I had followed devoutly for the first ten months of my firstborn’s life: trust no one to watch the baby other than my wife and myself. (We had made an exception for my mother-in-law, but I kept a sharp eye focused in her direction the whole time she held the baby in her arms.) Candidates for the title of "World’s Most Overprotective First-time Parents," we both agreed that even considering hiring a baby-sitter, after several rounds of grueling interviews, was off in the distant future—so how could I even raise the possibility of entrusting my child to the sort of seedy bum who would show up at a baseball-related event?

It was so shameful a response, I must confess, that I have never shared it with anyone before writing this article. I certainly couldn’t tell my wife about my moment of crisis when I got home that afternoon—and if she had guessed at it, I would have indignantly denied thinking the thoughts I had. "What? Endanger the baby? Trust some total stranger to take care of her? Bat against the greatest major-leaguer in history with her on my back? Are you insane, woman?" But think those thoughts, I did.

So after some interval that I prefer to believe lasted only a second or two, I held up my winning half-ticket and offered it to the crowd. For a moment, I was the most selfless of selfless men, and I had no trouble finding dozens of strangers eager to stand in against Seaver.

The outcomes of men in their 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s batting against a consummate professional were, by the way, a trifle surprising. I was 34 myself at the time, not far removed my peak of athletic ability, and I knew that a foul tip would have been a monumental achievement. Seaver warmed up, and nodded at the first batter to step into the box, motioning him slightly with his mitt. His face was all-business, and his first pitch was right over the plate, at what appeared to be blinding speed but which, in reality, was probably just a batting-practice fastball.

The batter swung at it a half-second after it had popped in the catcher’s mitt.

Seaver easily struck out the first few batters to face him, and, as hittable as I understood his pitches to be, I admired the courage of these men to stand that close to a Seaver fastball and to wave futilely at it. Maybe one of the first five batters got a splinter of wood on the ball as it made its way to the catcher’s glove.

But then something happened with the sixth batter that got everyone excited: one of the pitches that Seaver tossed over the center of the plate met a bat squarely. The ball rebounded straight back to the mound, but so quickly that Seaver couldn’t quite get a glove on it. It bounced once in the infield, hopped quickly over second base, and into the outfield. Seaver had no fielders behind him that afternoon, but even if he had, it wouldn’t have mattered. Someone had hit a ball off Seaver that no infielder could have caught, a clean single, right up the middle, any way you looked at it.

The crowd buzzed. "Did you see that?" "Man, that guy connected!" "Clean hit!" and so on.

The batter, just a balding, paunchy guy in his early 40s, couldn’t help but grin. He stepped out of the box a moment to admire his handiwork, the ball bouncing in straightaway center field.

Seaver motioned for him to hurry up and get back in the box. The guy still had one more swing coming to him.

Seaver, at this time, was less than a year removed from the major leagues. (As Elizabeth Lee was climbing out to make her debut, Seaver was sitting on the Red Sox’ bench in the 1986 Series, on the DL but still a member of the Red Sox AL championship team that fall.) He was in fine shape. He also had his competitive spirit, which I’m sure he still has to this day.

Do you want to guess where the next pitch was thrown? Yup. Seaver threw it high and tight, and the batter, just seconds ago so proud of his accomplishment, hit the dirt like a sack of cement. And unlike the previous pitches, this was no half-speed fastball lazily making its way up to home plate. This one CRACKED in the catcher’s mitt, letting us all see by comparison just how gently he’d been tossing prior to that pitch.

I remember the silence following that duster. Everyone took in a breath. What the hell had just happened? We saw the would-be batter slowly get up from the cloud of dust he had created, unharmed, tentatively getting to his feet.

We all exhaled that breath of air. He was okay.

On the mound, Seaver’s expression hadn’t changed. He looked in towards the plate, all-business again, and motioned for the next batter to stand in the box. But there was an almost imperceptible smirk on his lips, or perhaps it was just a twinkle in his eye, that told us all, "If you think this guy could ever touch a pitch I throw when I’m trying to get him out, you’re dreaming."

That guy, I’m sure, understood how close he had come to getting decapitated, and understood how much his "hit" against Seaver was an act of lordly generosity on the great pitcher’s part. I knew that if I had been that batter, and had felt a Seaver fastball whistling three inches from my skull, I would never forget it as long as I lived. I would wake up periodically in a cold sweat for the rest of my life.

I’ve lived thirty years since that day, and since I wasn’t standing in the batter’s box when Seaver’s fastball roared by in terrifying proximity, I’d forgotten many of the details, at least until I dredged up my memories this week, and researched the fine points of that long-past afternoon. I didn’t get Seaver’s autograph on my painting, nor stand in the box and face his pitching, but I did get a story out of it, one I’m pleased to be able to confess after all these years. And if my ex-wife reads these words, or if Elizabeth Lee happens to come across them, all I can say is that I’m sorry, my dears, for being such a terrible father, or such a loony baseball fan, that I ever considered the choices I’ve described here. You both deserved a finer man than I was on September 15, 1987.