Hate to be too much of an old fogey stick-in-the-mud here on this fine modr’n sabermetric site, but the old-time stats still have a certain sentimental appeal for me, maybe just because they’re old-time stats I grew up thinking were the be-all and end-all of baseb-all. Wins and losses (for pitchers), batting average (for hitters)—what can I say, something about them will always be dear to my heart. My brain, on the other body part, has long since accepted the discrediting of old-fashioned stats, but as you can see, I don’t really use my brain all that much in writing this column.

It used to be important—no, it used to SEEM important—if someone were a .300 batter. Nowadays, it’s a trivial point to fret over, much less obsess over, but early in most of our lifetimes, players certainly cared if they were batting over or under .300 when the season ended. They would strategize, they would insist on playing if they were at .299, hoping they could pull a 1-for-3 and then get pulled from the lineup, or if they were at .300, they could opt out of playing that final game, having nothing to gain and everything (again, it seemed like everything) to lose by playing that last game.

I’d bet there is a slight statistical bump at .300, a slight depression in incidences of .299, just because of players’ sometimes successful manipulation of their stats to finish over .300. I used to feel sorry for players whose seasons ended with them stuck on .299. I would think "How sad," (or sometimes with a player I disliked, "Good!") but it’s not just me who has grown from being a spiteful, nasty ten year old, it’s Batting Average that has changed from being the all-important measure of a batter’s worth to a negligible number, far behind OBP in importance, and OPS, and OPS+, and WAR and and and and.

Does it even gets mentioned anymore during contract negotiations whether someone barely cleared, or barely failed to clear, the .300 mark? There are a bunch of reasons the subject wouldn’t come up, in addition to B.A.’s decreased significance: all those other measures crowd up that conversation, and Park Factors and League Factors and lifetime performance stats influence negotiations much more than "Over or under .300?" does, but there is one way that B.A. continues to have significance, at least historically.

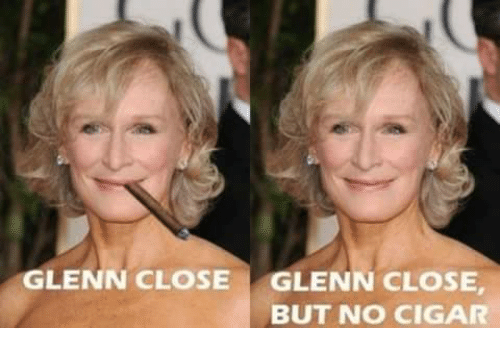

It still seems sad to me if a player ends his career close-but-no-cigar to the .300 mark.

Typically, this is a player who has hit above .300 for a decade or better, but who, in his declining years, watches his performance slowly erode until, at the very end, it dips to the very high .290s. The sad part, I guess, is that the player has conflicting emotions about prolonging his career—still capable of contributing with the bat, he must gauge whether maintaining his .300 lifetime mark is a worthy goal. Especially as Batting Average’s shine fades to an increasingly grimy gray, the modern player will say "Who cares?" and sign contracts until no contract is offered.

I once wondered, purely theoretically, about which choice a great hitter would make if he were threatening to surpass Cobb’s lifetime .366 figure and, at the same time, threatening to break Rose’s lifetime total hits mark, but where the one would necessarily endanger the other. As an illustration, say the guy had a lifetime Batting Average of .368 in his early 40s, and was also within 100 hits of Rose—the sticking point would be the fact that in recent years he hadn’t gotten his average very far above .300. If he stuck around long enough to accrue the 100 hits, his average would dip below Cobb’s mark, but if he retired while he still had a BA of .367 or better, he would fall short of Rose. All else equal, which is the more valuable mark to hold? And what if his dilemma got even closer? What if it came down to the final game of his final season, when an 0-for-4 would pull him down to .365, but a 2-for-4 would first tie him with Rose and then make him the all-time hits leader? Would he play or would he sit?

This dilemma is somewhat similar: a fading player foresees the day his lifetime average will fall to .299 or worse, knowing he can still contribute something to his team, but no longer provide the star-power he had supplied for years. This problem is not strictly theoretical: plenty of players end their careers with BAs in the high .290s, batters who had held a lifetime .300+ average for many years. The answer, in the case of current players, is to watch your average drop, and collect the paychecks until they stop. In recent years, Roberto Alomar (.3002), John Kruk (also .3002) and Pedro Guerrero (.3001) have retired while still barely on the plus side of .300 but to none of them did their precious .300 BA appear to play a big part in their deciding to retire when they did. Many more have continued to draw an MLB salary and witness their BAs sliding below .2995.

The archetype, for me, of such a player is Mickey Mantle, who ended at a .298 mark, unfortunately timing the end of his career to coincide with a historic dip in league averages: in Mantle’s final year, 1968, his .236 average was actually six points above the American League’s. Mantle cared a great deal about relinquishing that lifetime .300 BA. I’ve discussed before how sad finishing at .298 seemed to make him, and how silly a concern it seems to us today, as if we’d think any less of .298 Mantle but much more of the .300 version. He held onto it until midway through that final season, which he entered with a lifetime .302 (2312-for-7667). In 1968, he got off to a decent start, but slumped badly, falling to a miserable .193 average on May 12th, his low for the year, but he still held on to a legitimate .300 average, with still more hits to give up. (His May 12th mark was .30038.)

A little tedious research reveals that Mantle ceased to be a .300 batter for good in the seventh inning of a game against the Red Sox on July 22, 1968. (Not only was this moment not noted in any of the New York City papers I could locate in a cursory search, meaning I cursed several times in the course of it, but the game story and box score never even appeared in the New York Times, as far as I could tell.) After being struck out by Jim Lonborg in the first inning, Mantle still had his .300 average, rounded off (.299507,) but when Gary Waslewski got him to ground out to first (Dalton Jones unassisted) in the seventh inning, his lifetime average dropped to .299 (.29946) and would keep dropping throughout the season. https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NYA/NYA196807220.shtml . Immediately following that groundout to first, btw, George Scott came to replace Jones in mid-inning. I have no idea why. Dick Williams didn’t like the way Jones handled the ball?

Mantle’s birthday twin, Keith Hernandez (born exactly 22 years after Mantle), didn’t seem to feel that same sting as Mantle had, though Batting Average comprised much more of Hernandez’s offense than it did Mantle’s. Hernandez’s status as a .300 hitter is much dicier than I had thought: when he came over from the Cardinals in mid-1983, I thought of him a former batting champion (which he was--.344 in 1979) but actually his BA with St. Louis was just .299. It went up with the Mets in Shea (!), but only to a peak around .302 (may have gotten a point or two higher—I didn’t check on a day-to-day basis), He maintained his .300 lifetime average into his final year with the Mets, when a .233 BA knocked him off the .300 perch, and he retired the next year, finishing at .296 lifetime. If your peak is .302, then you’re almost certainly going to finish below .300 (unless you’re lucky enough to die in a fiery plane crash while still an active player, or something—see Costanza, George).

Mantle, OTOH, had a mid-career peak of .316, after his .365 in 1957, giving him a considerable cushion to chip away at. (Mantle’s day-to-day peak was actually a point or two higher than .316, around August 19, 1957, when he was batting .385, but you get the idea.) Beginning with 1958, Mantle batted .285, dragging his final lifetime average down to .298.

I’ll pick up the historical stuff later, but let’s look now at active .300+ batters (minimum 3000 PA) and speculate about their chances to end their careers keeping a .300 BA. Some will drop off. Which ones?

|

BBref rank

|

Name

|

(years MLB, age)

|

BA today

|

Chances of retiring at .300+

|

|

62.

|

Miguel Cabrera

|

(15, 34)

|

.3168

|

Mortal lock

|

|

64.

|

Jose Altuve

|

(7, 27)

|

.3164

|

Has a chance

|

|

75.

|

Joey Votto

|

(11, 33)

|

.3134

|

Mortal lock

|

|

91.

|

Ichiro Suzuki

|

(17, 43)

|

.3116

|

Mortal lock

|

|

116.

|

Buster Posey

|

(9, 30)

|

.3083

|

Has a chance

|

|

118.

|

Joe Mauer

|

(14, 34)

|

.3082

|

Mortal lock

|

|

143.

|

Mike Trout

|

(7, 25)

|

.3060

|

Dead .300 walking

|

|

146.

|

Albert Pujols

|

(17, 37)

|

.3050

|

Has a chance

|

|

149.

|

Charlie Blackmon

|

(7, 30)

|

.3049

|

Dead .300 walking

|

|

151.

|

Robinson Cano

|

(13, 34)

|

.3045

|

Has a chance

|

|

185.

|

DJ LeMahieu

|

(7, 28)

|

.3019

|

Dead .300 walking

|

|

189.

|

Ryan Braun

|

(11, 33)

|

.3018

|

Dead .300 walking

|

The four least likely to drop off are the four closest to retirement and with the most cushion: "closest to retirement" means they’ve also got the most at-bats, so not only do they have the fewest remaining opportunities to bring their lifetime averages down, those averages will decline more slowly. "The most cushion" just means that they’ve got the furthest to fall. So Cabrera, age 34 with over .017 points of cushion, is totally safe, and even safer is Suzuki, who may not even play in the majors any more and who has .012 cushion points. (Measured from .2995.) I’d put Votto and Mauer down as mortal lox as well (Suzuki’s an immortal sashimi), Votto because of the size of his cushion.

Votto is still going strong at age 33. He was batting .310 at the end of the 2014 season, and every season since then his lifetime average has actually crept UP, quite remarkable for someone in his 30s. He’s about as safe as safe can be. Give you an idea: assume he’s only halfway through his career (which is totally nuts, he’d have to play full-time until he was 45), so he’d have to bat 1) under .285 2) for eleven more years to get his lifetime average below .300, neither of which I see happening. Bbref.com projects him to bat .305 in 2018.

My only concern about Mauer retiring with a .300 average is the amount of cushion he’s already lost: after his first decade in MLB, Mauer had a .323 average, which seems an impossibly big cushion, but now he’s down to .308. Still he’s 34 years old, and .008 is a lot. I’ll be surprised if Mauer lasts long enough to lose .0085 BA points. Bbref.com projects him to bat .271 next season—if that’s close to correct, Mauer probably will retire before dropping below .300.

You might suppose Altuve would be a lock to finish his career over .300 as well, being at .3162 now, but he’s young, 27, which actually works to his disadvantage. Mantle, at age 27 after the 1959 season, looked pretty strong at .311, but he lost those .011 points, and a bit more, mainly because he played for nine more years. Altuve’s got more cushion, but it’s not hard to imagine that if this is his halfway point, he could well bat .284 for the rest of his career and bring his average down to .299. It’s certainly not going to go up much from here, except maybe in the very short run. Altuve could make it, or he could settle into a long decline of .280-.295 seasons with enough power to bring his lifetime average down below .300. The next few seasons will tell. He’s got a real good chance, but he’s not quite a lock yet.

Let me give another parallel to Altuve, because I understand how hard it is to accept that a batting champion, an MVP, a proven superstar like Altuve might face a harsh dropoff in his numbers at this point. His most similar player in BBREF is Billy Herman, likewise a proven batting star aged 27, just off consecutive seasons of .341, 334,. and.335, with a career figure at age 27 standing at .319: Herman dropped to .277 at age 28, and beginning with that year, batted ‘only’ .291 for the rest of his career, dropping him to his overall BA of .304.

The youngest players on this list, along with Altuve, are endangered for similar reasons: they’re closer than Altuve is to .300 AND they’ve got a lot of potential to play for a long time at sub-.300 levels: I have a particularly hard time seeing Blackmon and LeMahieu maintaining their .300+ status, partly because they’re by no means guaranteed of playing in Denver for the rest of their careers and partly because, even in Denver, they’re pretty close to the .300 mark anyway. LeMahieu is still benefitting from his breakout .348 average in 2016—otherwise his lifetime BA is in the .280s, (last year he rebounded to .310,) so my guess is he has plenty of sub-.300 seasons left in him.

Like him, Charlie Blackmon is benefiting from a breakout year (.331 last season). All of the young guys, with 7 MLB seasons behind them, are benefitting from getting off to fast starts, but history shows that only a few such players are able to sustain the Batting Averages of the first halves of their careers. Even Trout, the best and the most promising of these younger players, is only batting .006 points over .300 now, with a long ways to go. Historically, I’ve learned (I think), most star players lose a lot more than six BA points over the second halves of their careers.

It’s fun trying to figure out, nel mezzo del cammin, where exactly the mid-point of a player’s career is. After the players’ careers are in the books, it takes just a little effort to make that computation, and even less effort to approximate where that mid-point might be. And of course, it’s not particularly meaningful to find, the precise mid-point, though in graduate school, the finest professor I had, an absolutely brilliant guy named Gerry Chapman, who was primarily an 18th-century specialist, taught a graduate course in Shakespeare, where he would make a strangely big deal out of locating the exact mid-point of each Shakespeare play. He would harp on the significance of that mid-point, examining it closely for thematic implications, for clues to reading the play as a whole, for important imagery etc. I had a very hard time buying into Chapman’s thesis (mainly because the mid-point could be fudged by how the typesetter set the prose, or by textual variations, or any number of factors) but damn if that line at mid-point wouldn’t have unusual, often eerie, resonance. Of course, that’s mostly due to ANY line picked out at random in a Shakespeare play withstanding a close interpretation, and so I find it with mid-career at-bats. If you would take the trouble to locate the exact at-bat in the middle of a career, it would seem significant much of the time, though only because any at-bat would, if you tried hard enough to make it so. ("Ooh, look, Kingman struck out!" or "Ooh, look, Kingman hit a homer!" or "Ooh, look, Kingman flied out to left!" could all seem emblematic of Kingman’s career.)

This is all to say that I needed, in the course of this report, to locate roughly (sometimes exactly) where a player’s career mid-point was, because I had no clue what the dropoff in BA normally is between the halves of a given player’s career. Or even if there is normally a dropoff at all, though I suspected there must be: most players seem to have most of their career BA high-seasons early on, and those who have seasons well above .300 are able to linger for several years at the end with several seasons of averages well below .300 but still above the league average. Eyeballing it, it looks like a normal dropoff is about 20 BA points, though if anyone knows about systematic research into first-half/second-half differences, I’m all ears. I did do several quick-‘n’-dirty studies, approximating the breakoff points at the seasons’ ends that looks like the mid-points. (I.e., if someone played 14 seasons, I broke it down into 7 and 7, unless he had a lot of tiny seasons—10 games, 20 games—at either end of his career, in which case I’d break it down to 6 and 8, or 8 and 6, or sometimes, 5 and 9, whichever gave the most nearly even division of playing time. Players with odd numbers of seasons, I just tried to find the one point that gave the most even division of games, PAs, ABs, etc. I’ll run a few random samples of breakdowns of retired players (mostly around the .300 career mark) whom I looked at, so you can see what I’m talking about:

|

Player, years (1st half/ 2nd half)

|

1st half of career BA

|

2nd half of career BA

|

difference

|

|

Billy Herman (1931-7/ 1938-47)

|

.319

|

.289

|

+30

|

|

Frank Demaree (1932-7/1938-44)

|

.317

|

.281

|

+36

|

|

Ted Williams (1939-49/1950-60)

|

.353

|

.335

|

+18

|

|

Carl Furillo (1946-52/1953-60)

|

.294

|

.304

|

-10

|

|

Billy Goodman (1947-53/ 1954-62)

|

.314

|

.286

|

+28

|

|

Duke Snider (1947-55/1956-64)

|

.307

|

.283

|

+24

|

|

Willie Mays (1951-62/1963-73)

|

.316

|

.288

|

+28

|

|

Mickey Mantle (1951-8/1959-1968)

|

.314

|

.282

|

+32

|

|

Jim Rice (1974-81/ 1982-9)

|

.305

|

.291

|

+14

|

|

Keith Hernandez (1974-81/1982-9)

|

.299

|

.293

|

+ 6

|

|

AVERAGE

|

|

|

+20.6

|

So nine out of the ten hitters I looked at had a better BA over the first halves of their careers than the second halves, for an average of about .020 points. I also took a look at a few players whom I knew to have slow starts to their careers in terms of batting average, just to see how large a swing in the opposite direction I could generate with these players, all selected specifically for their late-career improvements in BA:

|

Player, (first half/second half)

|

1st half of career BA

|

2nd half of career BA

|

Difference

|

|

Bill Terry (1923-30/1931-36)

|

.341

|

341

|

--

|

|

Jim Hickman (1962-8)/1969-75)

|

.236

|

.268

|

-32

|

|

Roberto Clemente (1955-63/ 1964-72)

|

.303

|

.331

|

-28

|

|

Joe Torre (1960-68/1969-77)

|

.294

|

.300

|

-6

|

|

Matty Alou (1960-68/1969-74)

|

.307

|

.307

|

--

|

|

Ozzie Smith (1978-86/1987-96)

|

.247

|

.277

|

-30

|

|

Jeff Kent (1992-2000/2001-8)

|

.284

|

.296

|

-12

|

|

Paul O’Neill (1985-94/1995-2001)

|

.277

|

.299

|

-22

|

Remember, this second chart was players I selected specifically for their careers getting off to slow starts, batting average-wise, but much of the time even those players’ BAs stayed close to even in both halves of their careers: Terry and Em Alou broke about even, while three players I looked at because I thought they’d underperformed for a few seasons at the start, Hal McRae, Elston Howard, and Jose Oquendo actually still had higher BAs in the first half of their careers. Torre’s improvement over the second half is pretty small, as is Kent’s, while the size of Jim Hickman’s and Clemente’s second-half upticks are easily explained by factors outside of "improved hitting": Hickman spent the first half of his career in Shea and Chavez Ravine and the second half in Wrigley, while Clemente was saved (again, by disastrous aviation) from declining late-career seasons. (Though his second-half bulge was sizable enough to land him on this list even if he’d played into his forties with below-.300 BAs.) Only Paul O’Neill and Ozzie Smith remain as counters to the trend on the first chart, as players with substantial second-half BA improvements with no obvious explanation. If anyone wants to run further players who improved substantially over the second halves of their career, I’d love to see it, but for now, considering that one chart consists of random players and the other of preselected players I thought would show second -half improvements, I’m going to provisionally conclude that most players have a first-half BA improvement on the order of .020 BA points.

There’s a lot of approximating going on here: in addition to the halves themselves being imprecise (just the season’s end that looks closest to a mid-point), I’m also using rounded-off numbers in place of actually computing the BAs (that is, I’m using BBref’s three-digit figures for Herman’s 1931-7 BA, not computing them myself down to four digits), and I’m subtracting the first-half difference from the career total to come up with the second-half instead of figuring it out myself down to the fourth digit, which might result in an error of 1 or 2 BA points, and probably does. But since all I’m doing is looking for a rough difference in career-half BAs, 2 or 3 points doesn’t matter much, and overall the positive and negative errors will cancel each other out anyway.

This conclusion allows me to apply the principle to the active players over the .300 mark that those in mid-career will probably take a substantial dive in their BAs, and so will need a much larger cushion than just a few BA points. Altuve has a big cushion, but he probably (IMO) still needs to build on it for a few more years. Trout, at only .306 and only 27 years old, is cooked, in my estimation, certainly medium-rare unless he starts batting .340 or so in the next few years. Six points just won’t cut it. None of these seven-season wonders (Altuve, Trout, LeMahieu, Blackmon) is at the midpoint of his career quite yet, most likely, but they’re all are getting close, and that .020- point drop will kill their chances.

Pujols and Braun are similarly endangered: both are in the last phase of their careers, which is the only thing that will save their .300 averages. If their skills decline quickly, so quickly that they can’t stay in MLB more than another year or two, they may be able to retire as .300 hitters. Braun is in severe danger, being the closest to the .300 line. Through the first six years of his career, 2007-2012, Braun batted .313 but in the five years since 2012, he’s batted .283—since his cushion is so small, he could dip below .300 this season, if he bats in the low .270s with a lot of ABs. BBref projects his 2018 BA as .277, 116-for-419, which would bring him to 1815=for-6048, or .300099, so at this rate, Braun’s out after the 2019 season.

Pujols has more BA points, and is considerably older than Ryan Braun, so I make him safer to retire with a .300 average. Through his first nine seasons, 2001-2009, he batted a spectacular .334, seemingly an impossibly safe cushion, but in the last eight years, he’s fallen all the way to .273. Even more than Braun, he still hits for power, though BBref’s projection has him batting only .243 in 2018, so he might well stick around long enough to drag his average below .300.

Buster Posey still hasn’t entered the decline phase in his batting average yet, and the BBRef projection for 2018 (.299) doesn’t really do him much harm—yet. Still, it’s easy to imagine Posey playing for another nine seasons, getting another 4260 ABs, and winding up batting over the second half of his career below .292, which would bring under .300. I think that’s where the smart money is betting, for Posey’s decline to begin soon, for it to last about as long as his career to date, and for it to have him batting less than .292 from here on in.

Robinson Cano is an odd case: he hasn’t batted .300 since 2014, though he’s been close (.289 BA over the past three seasons) and he still has power, so I can see him playing full-time for several seasons with a sharply declining BA. BBref projection for 2018: .278. He and Mauer and Braun and are about the same age, 34, but Cano retains his peak offensive skills the best, giving him the longest projected career of the three with a declining BA. If, for convenience’s sake, we give Cano another 2200 more ABs, about 4 years of fulltime play (he had 2466 ABs over the past four seasons), that would put him at exactly 10,000 ABs lifetime. With 2376 hits today, he will need 619 hits in those 4 seasons (a .261 BA) to wind up at .2995. I’d say he looks pretty solid to bat over .261 in the remainder of his seasons, but it’s not a crazy-low figure for Cano. It looks possible, and it also looks possible for him to go over the 10,000 mark in ABs, which would mean that he could bat a few points higher than .261 in the remainder of his career and still get pulled down below .300. I don’t think he’s going to make it, but he stands a better chance than Braun.

There are three Red Sox just about at the .300 mark, two of them retired, one of them active: Billy Goodman, who’s the lowest rounded-off .300 batter on the BBRef list, Jim Rice, and Dustin Pedroia, who now stands at .300333etc. I didn’t put DP on my list of active .300 hitters, mainly because I neglected to, but when I caught it, I realized he’s a whole ‘nother category, below even "dead .300 walking." There’s just no way, apart from a Lazarus-like event, that Pedrioa’s average WON’T fall below the .300 mark, and the interesting thing about Pedroia is that we can keep an eye out to see just when that at-bat will occur, very likely this season.

Conveniently, Pedroia has as of this writing exactly 6000 ABs and 1802 hits, so it’s easy to compute by eye just how close he is skating above a .300 BA. In the past four seasons, he’s batted .296 (.293 last year), meaning he’s still good enough to play a few more years, but not good enough to keep batting over .296 as he goes through a decline phase. If he starts off 2018 slow (by going, say, 15-for-67, a .224 clip), his lifetime BA will drop to .29949, and that will be that.

Pedrioa is injured this winter (recovering from knee surgery, he’s supposed to be out until late May) so he might just get off to a slow start. Bbref www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/pedrodu01.shtml https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/pedrodu01.shtml projects him in 2018 to have 130 hits in 447 ABs (.291), but that seems pretty rosy from here. I don’t know how much (or if) Bbref’s projections are purely mathematical or if they account for meniscus surgery, but as someone now recovering from a torn meniscus myself, it is a slow and painful process, likely to impair DP’s ability to turn the DP and to play second base effectively all by itself. Apart from the meniscus, though, other issues leading to a sub-.300 year are Pedrioa’s age, 34, his decline generally (no All-Star appearances, MVP votes, Gold Gloves since 2014), and the fact that second base is a particularly tough position to play into one’s mid-thirties. I’m a huge fan of Pedroia’s but I must admit that I wouldn’t put much above a nickel on him retaining his .300 lifetime BA very far into the resumption of his playing career. The only way for him to retain it is either to retire immediately, which is very unlikely, or to bat better than .300 from here on in, which is even less likely.

A predecessor of Pedroia’s at second base for the Sox, Billy Goodman has the distinction of skating the closest to the surface of .300 of all the players on the list, at .299610. One more ohfer-three and Goodman would sit at a rounded-off .299. Goodman’s SABR-bio doesn’t mention whether saving the .300 BA played any part in his decision to retire at the end of the 1962 season, but he was 37 years old and had batted .250 during the previous four seasons, so it was probably just a happy coincidence for him.

In Jim Rice’s final season, 1989, through May 3rd, his totals were 2432-for-8120, which came to .299507, but the next day, in a Nolan Ryan-Roger Clemens matchup at Fenway Park https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS198905050.shtml, Rice grounded to 3b-man Steve Buechle in the bottom of the 2nd, bringing his lifetime BA down to .299470. It would stay below .300 for the remaining 30 games of his career (during which Rice would bat only .190, dragging his MLB total to .298.) Sad.

The two saddest sacks of all are the two whose BA rounds off to .299-and-less-than-a-half, Carl Furillo and Frank Demaree, one of whom I heard about all my life, the other of whom I’d never heard of before this week. After batting .322 in 1949, Carl Furillo had a lifetime BA over .300, and he held onto that for over eleven more years: he ended 1959 still batting a (rounded-off) .300 (.29962). In the 1960s, though, which for Furillo meant April and the first week of May of 1960, he batted only .200, 2-for-10, and lost his rounded-off .300, retiring with a .29947 BA. The end of Furillo’s career generally made him something of a Sad Sack character to me—the Dodgers released him but he claimed he was injured when released so they owed him his full salary, not just the part up to the day they let him go, so he sued the team, and won, and they paid him, but he never got a scouting or coaching job from any MLB team, died a pissed-off guy (according to Kahn’s BOYS OF SUMMER)—what a total mess! Before he died, he worked construction on the World Trade Center, the same summer that I ran lunch orders for my dad’s restaurant in lower Manhattan, delivering meals and coffee to the WTC workers as it was going up. I think Carl was more of a lunch-pail guy than an order-in kind of guy—I might have seen him if I’d been looking, but I never met the man.

I noticed, reviewing his numbers, a certain superficial resemblance to Keith Hernandez’s: mainly just the single batting championship, both at .344, that was head and shoulders above the rest of his career, which for both Carl and Keith was just under .300. Same sort of power, Furillo a few more homers (but played in a good HR park), a similar OPS (.821/813), similar RBI total (1071/1058), both the best throwing arm at their positions. A pure coincidence, they weren’t really the same type of guy, Hernandez more a top of the order, get on base, kind of hitter, Furillo further down in the order, drive-em-in kind of guy, but I suppose there are few pairs of players who you couldn’t find a few such coincidences with, if you looked hard enough.

Furillo actually got a base hit in his final MLB at-bat, placing his dip below .300 earlier in the week, but Demaree, a pretty good outfielder with the Cubs in the 1930s (All-Star in 1936 and 1937, playing every game and batting .337 with 211 RBIs in those two years), waited until his final at-bat to dip to .299467. History (or BBref.com) doesn’t record how he made that out, only that he made it in Comiskey Park against Eddie Lopat of the White Sox on a June afternoon in 1944. He’d made two outs previously that day, bringing his lifetime BA to .2995413951243061 (1241 for 4143), and I’m sure if he had known what his final out that day would do to his .300 average, or that the Browns, in the process of winning their only AL pennant, were going to release him that evening, he might have requested that his manager replace him in the lineup before rather than after that at-bat. But he didn’t, and he didn’t, so there Frank Demaree stands, just below the cut-off that we all used to recognize as baseball’s most emblematic batting mark.