I wanted to check out major-leaguers’ (HoFers’, actually) accounts of their MLB debuts, for reasons I’ll go into in a bit, though such juicy tale-tellers as Ty Cobb and Casey Stengel predate the play-by-play rundowns that make the tracers possible. So I ran a few tracers after the late 1920s for some stories featured in Voices from Cooperstown, the book of verbatim accounts that I was running HBP tracers from a few weeks ago.

Mickey Cochrane’s 1925 debut also predates the play-by-plays, but one detail he tells, his "singl[ing] to left, driving in the winning run" in his first game, contradicts the known facts in that Cochrane isn’t credited with an RBI that day. He did get a hit, pinch-hitting for Cy Perkins, whose job he soon took, as he says, and it seemed to be off pitcher Rudy Kallio, as he maintains. But no RBI.

Cochrane says (on p. 48):

Came the eighth inning and the Red Sox had tied the score. In our turn at bat the bases were loaded when came Cy’s turn to hit and Connie Mack commenced to looking for a hitter. On the mound, working for the Sox was Rudy Kallio, and Rudy had been something of a cousin of mine on the Coast [P.C.L.] in 1924. When Connie looked over the bench for a pinch hitter, I remarked, ‘Give me a bat, I can hit that guy."

"All right, son," said Connie. "Go up there if you think you can."

I went up and singled to left, driving in the winning run.

Far from tying the score in the eighth inning, the Red Sox had been leading the A’s all day, by as much as 6-0 in the middle of the seventh, when the A’s scored two runs in the bottom of the inning. The Sox increased their lead to 7-2 in the eighth, when Cochrane presumably was sent in to pinch-hit for Cy Perkins, as his opening sentence above claims. Apart from not getting an RBI during this game, there’s another problem with Cochrane’s story: the Red Sox used three pitchers to get through the eighth inning, none of them Rudy Kallio.

Kallio got into the game with one out in the ninth, when the A’s tied up the score, and pitched the rest of the game, into the tenth inning, losing it on "three hits that settled the contest," according to the New York Times of the next day. The account doesn’t name the A’s hitters, but it (like bbref.com’s box score https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHA/PHA192504140.shtml) doesn’t credit Cochrane with an RBI.

So the central moment in Cochrane’s narrative, his persuading Mack to kindly let him bat because of his PCL success against Kallio almost certainly doesn’t add up. Cochrane got two at-bats and one hit in the game, which ended with one out in the tenth—there’s not enough room for him to get both at bats against Kallio, who got only three outs in the game.

Put differently, if Cochrane drove in the winning run in the 8th inning, Kallio couldn’t have been in the game yet and the game couldn’t, of course, have gone into extra innings. If Cochrane’s hit came in his second at-bat, against Kallio, he obviously would have been in the game already, so no need to plead with Mack to insert him. What probably happened, just my guess, is that, having been inserted into the lineup before Kallio came in, Cochrane made an out of some sort against one of the Red Sox pitchers who pitched part of the eighth and then, facing Kallio in the tenth, made a hit that moved the winning runner up a base or two and then was left on base when someone else drove in the winning run against Kallio. Cochrane is credited with neither an RBI nor a run scored in the game.

There’s still no play-by-play in 1926, for Joe Cronin’s debut, but he too gets stuff wrong about "[m]y first day in the big leagues," when, he claims, "I subbed for Glenn Wright against the Reds. Threw one ten feet over the first baseman’s head. Booted a grounder" (p. 49).

That’s all he says about his first day in MLB, but aside from substituting against the Reds, he gets every detail wrong: he couldn’t have committed two errors substituting for the Pirates’ shortstop Wright, because he came into (and out of) the game as a pinch-runner (for catcher Earl Smith, who was then substituted for in the field by another catcher), and Wright played the entire game at shortstop. Kind of tough to muff plays when you don’t get to wear a glove in the field, no? Cronin’s first four MLB appearances, in fact, were all exclusively as a pinch-runner, on April 29 and 30 and May 7 and 8, when he was sent down to the minors for a while, and his first game back on July 20, 1926 https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PIT/PIT192607200.shtml , he did get into a game subbing as a defensive replacement for shortstop Wright, but he didn’t make one error, much less two. Wright, however, is credited with making an error at shortstop that day. Equally tough to see how Cronin might have remembered Wright’s fielding mishaps as his own, though.

BBREF’s notation system puzzles me. They seem to credit Cronin with playing that entire game: his innings are described as "0-GF" which looks like it means that he "entered the game in the starting lineup, played until the finish of the game," except that "CG" is their notation for that. Anyway, the boxscore has him listed as a sub for Wright, who has three at-bats while Cronin has one. Both are listed at "SS" for defensive position. (Maybe the "0" in "0-GF" is a placeholder, meaning "we don’t know when he entered the game but he played until the end"?)

Cronin next appears as a defensive sub for Wright in a 14-2 blowout win against Brooklyn. Again, he isn’t credited with making a single error, much less two. And it’s hard to see how a ball "thrown ten feet over the first baseman’s head" doesn’t get scored as an error, or booting a grounder. Both are possible if the runner would have, in the scorer’s judgment, reached base anyway and didn’t advance beyond first base, neither of which is likely, both of which are extremely unlikely. In any event, he’s now played two games at shortstop, subbing for Wright without an error, though these games are against Boston and Brooklyn, anyway, not Cincinnati.

He doesn’t play again until August 2nd, https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHI/PHI192608020.shtml when he comes in against Philadelphia as a defensive substitute at 2B, again making no errors, though this time Glenn Wright makes two errors at shortstop, his 34th and 35th of the season, which seems like a lot for August 2nd, and Pie Traynor also commits two errors. Difficult, again, to see how Cronin confuses these veterans’ errors for his own, but his fielding record is still perfect, far as I can tell. (His batting record, as of his seventh MLB game is still stuck at .000, too.) Anyway, the Pirates don’t even face Cincinnati again until more than another month passes—starting on September 8th, Cronin is credited with playing a complete game (three CGs, in fact) against the Reds in that series, so again I can’t see how he subs for Wright.

Cronin’s account of his first MLB game is all screwed up, though I don’t doubt that he committed a fielding error and a throwing error in the same game at some point in his career—just not in his first MLB game against the Reds in April of 1926. Cronin mostly played 2B in 1926, not much shortstop (192 innings vs. 14) and all three of his errors that season occurred at 2B. Glenn Wright never played second base for the Pirates, so he simply didn’t "sub for Wright" and make two errors in his MLB debut or any other game that year.

The next checkable account in the "MLB debuts" chapter is that of Ted Williams, who gets the opponent and the pitcher right, but overdramatizes one detail: "Anyway, first time up, [Red Ruffing] strikes me out on three pitches. Second time up, same thing." Ruffing did fan him his first MLB at-bat (I don’t know how many pitches it took) but not the second time. That’s the overly dramatic build-up, that little extra bit of tantalizing but fictional detail. After fanning the first time, Williams returned to the Sox dugout where a veteran, Jack Wilson, was needling him about how major league pitching is better than the 20-year-old Williams is used to, and Williams quotes himself as responding, "Screw you. I know I can hit this guy." Which he did. His second MLB at-bat against Ruffing, he got a double between the Yankees’ centerfielder (Joe D.) and the rightfielder, or as Williams puts it, "I hit him real good, and after that old Wilson stopped agitating me." In his THIRD big-league at-bat, Williams struck out again against Ruffing, but isn’t it a better story if Williams strikes out his first two times and hits the double his third time to the plate?

Musial’s account of his debut seems pretty clean, though lacking a play-by-play to check it against: according to the box score, he did go 2 for 4, as he claims, for a .500 batting average at the end of his first game. So did Duke Snider, 1-for-2, but Snider’s debut story suffers from a little statistical puffery: he notes that he got a hit in his first appearance, during Jackie Robinson’s big league debut, which is the accurate part. But he says he sent a newspaper clipping to his mother, "and wrote that Jackie got all the ink, but I was outhitting him. I was batting 1.000," adding a mere .500 points to his MLB average. He had been batting 1.000 after his first at-bat, but in his second at-bat that game he grounded out to second base, so at the game’s end he had a .500 batting average. Whether he misled his mother or his interviewer, or both, is anybody’s guess.

Whitey Ford remembers his debut https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS195007010.shtml against Boston, coming in "the fourth inning, when we were losing something like 11-2," which is a little off. He came in during the second inning and the Yankees were losing by only 6 to 1 at the time. I guess 6-1 is "something like" 11-2. (Walt Dropo had hit a grandslammer off Tommy Byrnes in the bottom of the first). Ford gets the batter and the baserunners pretty good: "Vern Stephens was on third base, Walt Dropo was on first, and Bobby Doerr was the batter." When Whitey entered, Stephens was actually on second base, but Whitey’s first order of business in MLB was to throw a wild pitch, moving both runners up one base. He then, as he says, gave up a two-run single to Bobby Doerr, and the Yankees ended up losing by 13-4, not the "17-4, something tidy like that" that Whitey remembers.

The chapter on HoF debuts ends with Al Kaline’s account of his: Kaline says he signed his contract with the Tigers that day in Baltimore, his hometown, and then took the train up to Philadelphia, where the Tigers were playing the A’s. It was a night game, so that part of the story is perfectly plausible. Some details in the next part, though, are contradicted by the box score: "I sat on the bench keeping my mouth shut until the seventh inning, when Freddie Hutchinson, the manager, who I don’t think even knew my name, said ‘Kid, come over and grab a bat, you’re hitting for the pitcher.’" Kaline says he "swung at the first pitch, flew out to centerfield, and I was so happy. Happy just to get it over with and get back inside the dugout….The next night I went into the outfield as a defensive player…." In fact, as the play-by-play reveals, https://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHA/PHA195306250.shtml , Kaline didn’t pinch-hit for the pitcher in his MLB debut—rather, he got into the game in the sixth inning, not the seventh, and as a defensive replacement for the Tigers’ centerfielder. His first big league at-bat came leading off the ninth inning, when he did indeed fly out to center on the first pitch he saw.

I find debut stories especially interesting because they illustrate moments in players’ careers about which they say, as Ted Williams did, "I never will forget." As we can see, they uniformly do a pretty good job of forgetting details, some large and significant, others tiny and inconsequential. In many ways, this moment is the one that they’d been waiting their entire lives for, the first moment they could legitimately claim to have been major league players, an ambition they’d been dreaming of, asleep and awake, for the first twenty-odd years of their lives. Players treasure keepsakes from these moments-- balls, bats, uniforms, caps—objects that often get preserved in these players’ trophy rooms. The details of those moments, they assure us, have been burned permanently into these players’ brains, details that get told and retold forever. This is not, in other words, just another moment of their careers, yet as we have seen, there is typically a detail, often a crucial one (or two or three), that is flat-out wrong in their memories of this event.

Mind you, I’m not advocating making a federal case about these lapses of memory: forgetting details is a human trait, and these players are merely displaying their humanity through their imperfect recall. What it does signify, however, is the frailty of memory in any circumstance you might want to know about, since these moments I’m selecting here are extremely well-documented (cf. Snider’s clipping that he mailed to his mother), extremely important in these players’ lives, extremely obvious to the players that they are being interviewed for a book, etc. There may be no memory that I can think of that someone could be expected him to recall any more sharply than a major leaguer recalling his first big-league appearance.

So when you’re listening to anyone’s recollections—a witness in court, a government official on TV, a reliable neighbor passing along gossip as best as he remembers it—the one thing you can be sure of is that his or her account of what happened is very likely flawed in at least one detail, and maybe in several crucial details. No matter how sincere or truthful someone might seem, a policy of "Trust, but verify" would be called for.

There is, however, an occasional bit of, shall we say, "active malfeasance" going on here. (Five syllables for "lying.") For example, after he gives the snippet quoted above (in full), Joe Cronin goes on to supply another memory that is both seriously flawed and very seriously self-aggrandizing:

To tell you the truth, I’d rather remember my first big day against the Yankees. We had a doubleheader and I hit six for eight with three triples that day. Hit them all three to right center. I can still hear their manager, Miller Huggins, yelling from their bench with his high squeaky voice, "Coive him. Coive the busher." And I just dug in harder and thought to myself, Go ahead. Give me your best. That was in the fall of that year, 1928, and I think those two games had a lot to do with them looking me over pretty good in 1929.

This one was easy to trace. Among the rare details are the three triples in a doubleheader and the very specific memory of Miller Huggins’ distinctive voice insulting Cronin. Huggins was managing the Yankees when Cronin got traded to the AL in 1928, and he managed until late 1929, dying before the season was over, so there’s very little possibility of Cronin merely misremembering an incident that happened with Huggins at a later point in his career. The games could have taken place, then, only in 1928 or 1929, and Cronin places it in the fall of 1928. Needless to say, he never hit 3 triples in two consecutive games in either year. The likelihood is that he’s describing the doubleheader between the Yankees and the Washington Senators that took place on September 7, 1928: Cronin had a pretty good day. He went 3-for-7 with one extra-base hit, and it was indeed a triple. The Senators swept the Yankees, 11-0 and 6-1, so Cronin had every right to feel good about his team, and the pretty good day he had.

But a pretty good day is far from the spectacular day he describes to his interviewer. 3-for-7 is far from 6-for-8, and three triples is a long way from one triple. Cronin seems to be fabricating pretty freely, and this one is hard to justify as an innocent slip of the memory. In many of these examples, the mental lapses make the games appear to be more productive than they actually were: Cronin’s three triples, Snider’s 1.000 average, Cochrane’s ghost RBI. And where they make the low points worse than they were, the facts seem re-arranged to make the story more colorful: Cronin’s two fielding errors, Williams’ two consecutive strikeouts. Very rare is the mistaken memory that adds or subtracts nothing from the quality of the player’s performance.

A few years after his debut, Mickey Mantle remembered a weird turn of events involving the woeful St. Louis Browns, whom he calls "probably the worst team I ever saw" (p. 185). His career and the existence of the Browns overlap for only four years, 1951-54, so it was pretty simple to trace—nineteen (or so) game winning streaks don’t come along that often, even for the Yankees. The one Mantle is talking about took place in May and June of 1953, and was immediately followed by the Browns coming into New York City for a four-game series:

One year I remember we had won nineteen straight games, which might be a record, and those old Browns came to New York for a series. So we figured there’s at least four more. Well, they beat us four in a row.

Is that ironic, or what? Ha, ha, on the Yankees, getting swept by the worst team Mantle ever saw!!

Problem, natchurly, is that 1) the Yankees didn’t have a nineteen-game streak—they won a mere 18 straight, a perfectly understandable innocent exaggeration, but 2) while the Browns DID break that streak, coming into New York for a four-game series, the last three games of the series were Brownie losses, not Brownie wins.

Again, what Mantle has done here is to take a somewhat ironic event, the last-place Browns breaking the first-place Yankees’ winning streak, and turning it into a four-game sweep of the Yankees, which would have been pretty astonishing, if it had actually happened. (And actually the Browns were in seventh place, well ahead of the last-place Tigers, who btw, were the next team to win a game against New York. The Browns might have been the worst team Mantle ever saw, but they were 4 ½ games ahead of Detroit in mid-June.) This is the traditional tall tale, whose day I think is over—my impression is that these stories got invented, and retold (until perhaps the tellers actually believed them) because the actual records were not easily available. Today, if Mike Trout tries to pass off a whopper like this, six reporters are going to google the boxscore on their phones and correct him as soon as he says "nineteen-game streak," so Trout doesn’t even think to go there. (The Yankees’ 1953 schedule and results are here: https://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/NYY/1953-schedule-scores.shtml .) At the end of June, as you can see, the Yankees did lose nine straight games, all to their first-division rivals Cleveland, Chicago and Boston, a slightly different sort of irony, and probably what Mantle mixed up with the surprising loss to the Browns.

A final non-debut story is told by Burleigh Grimes, a fascinating peripatetic Hall-of-Famer (missing only the Phillies and the Reds in his 19-year NL career) about his salary wars with Brooklyn owner Charlie Ebbets (p. 220-21):

I was pitching in Ebbets Field, and I think the score was 1-1 against Cincinnati. Jake Daubert was up, and Ebbets disliked him. He’d traded him away earlier in the year, in fact—a little disagreement over money. Anyway, I pitched Jake a slow ball, and he hit it off the right-center field wall for an inside-the-park homerun. Ebbets had a direct phone line from his box to the bench, and he used it to order them to pull me out of the ball game. I guess that was the only ball ever thrown over the top of Ebbets Field.

Mr. Ebbets fined me one thousand dollars. I didn’t say anything about it till the next spring.

I started off that next season with eight or ten wins in a row, and then I went on strike….

OK, the parameters are clearly laid out here: this took place in the 1919 season, based on Jake Daubert being traded from the Dodgers (mostly called the Robins at the time) to the Reds on February 1, 1919. The largest problem with the story as Grimes tells it is that the Reds played only one game in Brooklyn that year in which Grimes pitched, and he pitched a shutout, so obviously he gave up no home runs, to Daubert or anyone else, in any home game that season. And in fact Grimes didn’t give up a homer to the Reds all year long either in Cincinnati or in Brooklyn.

I won’t take you down all the rabbit-holes I traced this story through, but at the end of them, I found the game that Grimes is describing: it took place late the next season, September 16, 1920, kind of a long time for Charley Ebbets to hold a grudge against Jake Daubert, no? (I also learned how to pronounce "Daubert," which I’d been giving the full Stephen Colbert treatment, "doe-BEAR," but BBREF has it "DOW-burt," a good American name. I might have pronounced the Americanized version to rhyme with "Robert," but no, that’s only one thing I learned here: "Dowburt.") I mean, it’s a long time from February 1, 1919 to September 16, 1920 to stay pissed at someone over a salary dispute, especially someone who had been the MVP of an earlier season for your team, as Daubert had been.

According to the New York Times of the next day, however, far from a long smash against the rightfield wall in Ebbets Field, Daubert got his inside-the-park homerun the usual way of ITP homers: "Daubert followed with a low drive on a line to short left, which went for a home run. [Leftfielder Zack] Wheat missed a shoe-string catch. The ball bounded past him to the temporary bleachers in left field."

It’s hard to see how Ebbets could get angry at Grimes for giving up a single that Wheat misplayed into a HR, so furious that he ordered Grimes removed from the game via the modern miracle of the telephone, and that part of the story is pure fiction: Grimes remained in the game to its conclusion, another five innings past Daubert’s home run.

The fictional part is the whole reason that Grimes is telling the story: his conflict with Charles Ebbets, which he took to the next season by going on the strike, is his basis for describing the "1919" Daubert HR resulting in a thousand-dollar fine that caused Grimes to go on strike after peeling off an 8-0 or 10-0 record the next year. Problem here is that in neither the 1920 or 1921 seasons does Grimes begin that way, though he got off to good starts both years, starting the 1920 season 2-0 and 7-2, and the 1921 season 3-0 and 12-2, with no significant missed starts amounting to a "strike" of any sort. I’m sure some sort of dispute involving a fine took place, but this story’s clues do not lead to that dispute.

Running these tracers is a special kind of fun, incidentally. One pleasure of running these stories down is getting to root around in the old box scores and play-by-plays, and realize for the twelve thousandth time, how rich and complex baseball history is when it’s viewed from up-close. Reading about Pie Traynor in the first Cronin tracer, I get to remember that he wasn’t at the time an iconic, ensconced Hall of Fame third baseman, just another excellent player, pre-All-Star games, pre-MVP awards, pre-Hall of Fame. Contemporary fans may well have argued whether he was better than Glenn Wright, the cleanup-batting shortstop who suffered from mid-career injuries to the point that we hardly recognize his name now in comparison to Traynor. Reading a boxscore in which Traynor hits a popup in the clutch or boots a few groundballs, I’m reminded that, like any other star, he may have had a few fans displeased with his quality of play, maybe even gotten booed from time to time. Boxscores tend to humanize Hall-of-Famers. Especially in the days of eight-team leagues, you can often see three or four Hall-of-Famers on each team in a game, and sometimes they look like just-plain ballplayers in the boxscore. (Williams’ debut featured 10 eventual HoFers in the starting lineups—if you like, you can guess who they were in the "Comments" section, and I’ll tell how you did.)

But it’s mainly the names of stars and non-stars in the boxscores that please me. It was fun to see Walt Dropo hitting a first-inning grand-slam against the Yankees in 1950 for the Sox and then re-appearing as a Tiger in Kaline’s first MLB game, batting cleanup in the Tigers’ order, with Johnny Pesky batting and playing second. It was fun, as a Mets fan, to spot a 17-year old pitcher in that Tigers-A’s game making his debut a few minutes after the 18-year-old Kaline entered the game, a pitcher who would finish up his career ten seasons later with the 1962 Mets, the elder of their two Bob Millers. Or Lefty Grove, a rookie in Cochrane’s debut game in 1925 (though spelled "Groves" throughout the New York Times’ article) is a creaky veteran in Ted Williams’ debut—stuff like that.

It was also fun to realize what I was doing as some of these games took place. I was a week old during Kaline’s debut game, so I imagine that I was still being fussed over in my parents’ house pretty steadily at that point. The Yankees’ series with the Browns ended one week earlier, on June 18th, 1953 (the Yankees taking the series 3 games to 1, you’ll recall, sweeping a doubleheader with back-to-back shutouts), which was the day that I was born a dozen miles from Yankee Stadium as the crow barks.

I know that was a very hot day, not from the Yankees’ boxscore, which lists "Start Time Weather: Unknown", nor from my mother’s frequent complaints of how hellish it was for her to be in labor in the middle of a heat-wave (and Madison Park Hospital on Kings Highway still un-air-conditioned!), but strangely enough from Sylvia Plath’s novel The Bell Jar which opens famously with the sentence "It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn't know what I was doing in New York." The Rosenbergs were executed on June 19, 1953, the day after the Browns series ended, and the opening day of a series against the Tigers in the Stadium, the Yankees continuing their hot baseball in the "queer, sultry" weather that whole week. (The Dodgers, playing in St. Louis that afternoon, had a game-time temperature of 100 degrees. The whole country was in the grips of a massive heat wave https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/ecb5/88df40aca4ff97cd4104589f8bc201a6a5bc.pdf that June.) The execution of the Rosenbergs is also the central (and titular) event in the Robert Coover novel I keep mentioning (three articles in a row, a new BJOL record), The Public Burning, a fabulous (if occasionally disgusting) view of American life in the early 1950s.

Looking over boxscores from the week I was born, prompted by two of these tracers taking place in that week, two things stand out: the incredibly low attendance at major league games, and the incredible quick pace of games. Almost every box score I looked at showed a game time of under two hours, which is near-miraculous today. The Red Sox and the Tigers did play a three-hour game (3:03) the day I was born, but they had a good excuse: leading the Tigers 5-3 in the seventh inning, the Red Sox enjoyed a 17-run 7th. Gene Stephens went 3-for-3—in that inning! More amazing is the attendance: on Thursday, June 18, 1953, there were eight major league games played (the Yanks and Browns played a Thursday doubleheader, and the Braves and Phillies were idle) but the attendance was under 35,000. That might not seem very low, but I’m not talking about average attendance—that’s the total figure for all of major league baseball! Fewer than 2,500 people were in attendance to see Al Kaline’s first MLB appearance, and the entire three-game series drew only about 7,000 paying customers.

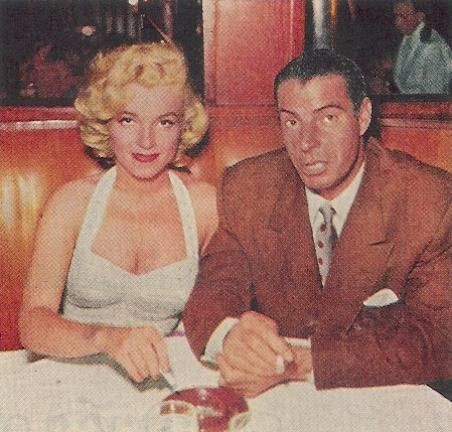

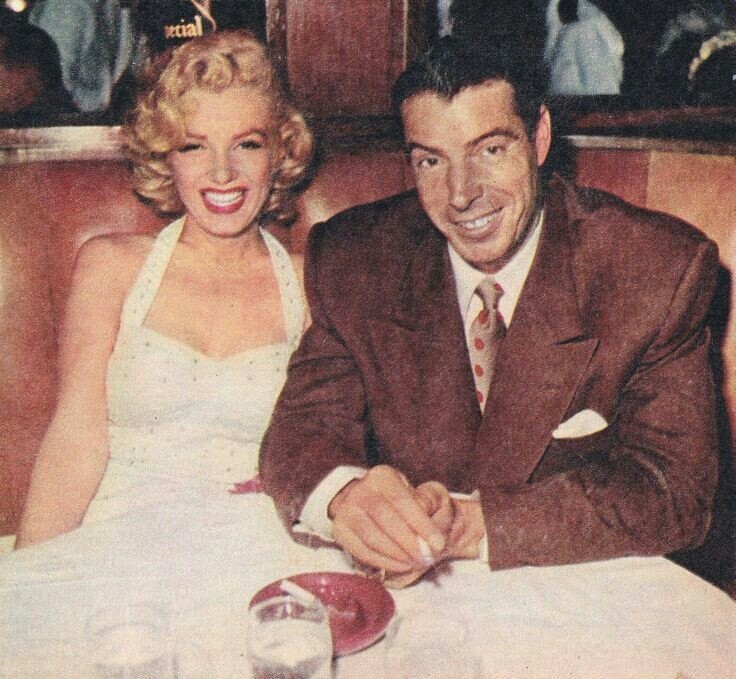

Of course, I can only imagine what my parents’ house was like the day of Kaline’s debut, but strangely enough I have a very clear idea of what I was doing the next day. Someone recently posted on Facebook a photograph of Joe DiMaggio dining in Chasen’s restaurant in Hollywood with his lovely fiancee on June 26, 1953, and I instantly realized exactly what I was doing that day.

How could I possibly recall precisely what I was doing on a day so soon after I was born? I have a very clear idea, if not a clear memory: I was attending a party, one at which I was the guest of honor. It would have been impossible to hold the party without me.

Eight days after my birth, I was the center of attention at my b’ris, the sacred covenant all Jews since Abraham have made with their Lord God, having a vital portion of my genitals severed by an old man with a long white beard and a straight razor. If I was anything like every other eight-day-old boy I’ve witnessed getting circumcised, I screamed like a stuck pig and shut up soon after receiving a tiny dose of schnapps in my squalling mouth. So: my first drink, my first medical procedure, my first exposure to a rabbi’s yammering, all as Joe and Marilyn made eyes at the cameras in a Hollywood lounge.

This is the pleasure of immersing myself into some past day: I can always find some detail worth dwelling on and marveling over, and the deeper I search, the more I can find.

I think there were dozens of cousins, neighbors, uncles, aunts, in-laws, and outlaws at my b’ris, probably not as many as had attended the Tigers-A’s game the previous day (2,368) but then I wasn’t offering an early glance at Detroit’s future Hall of Fame rightfielder. That’s my debut story, and I’m sticking to it.